Key Highlights:

- Historic First Enforcement: On December 5, 2025, the European Commission issued its first non-compliance decision under the Digital Services Act, fining X platform €120 million ($140 million) for breaching transparency obligations—a watershed moment in digital governance.

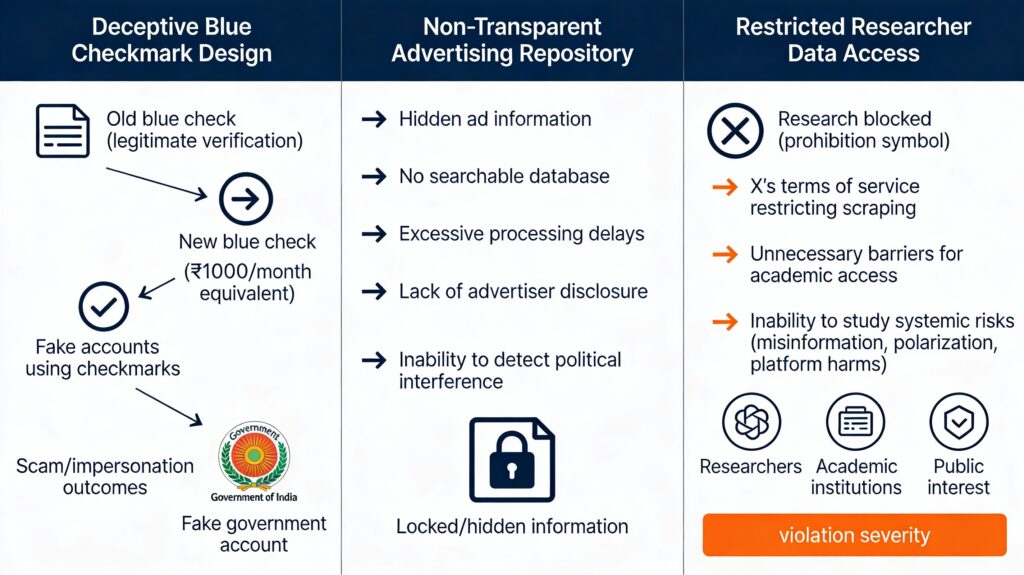

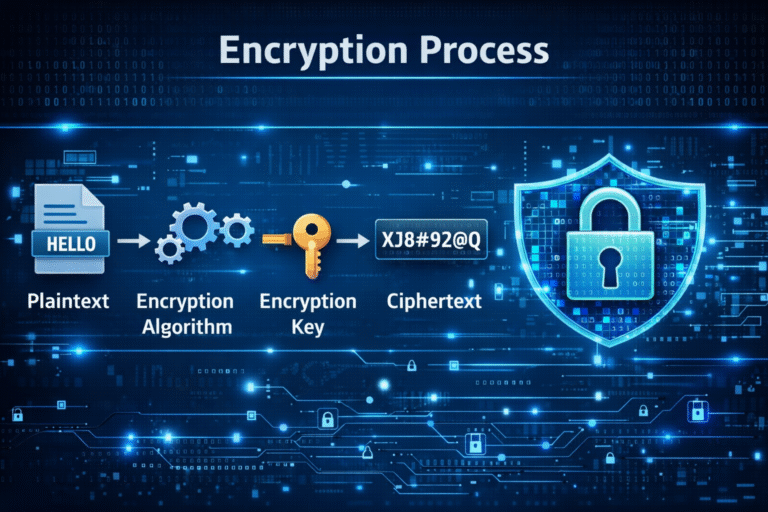

- Three Core Violations: (1) Deceptive blue checkmark design: Anyone can purchase verification without meaningful identity verification, deceiving users about account authenticity; (2) Non-transparent advertising repository: Hidden ad information, excessive processing delays, no searchable database preventing detection of political interference and manipulation; (3) Restricted researcher access: X blocks academic researchers from accessing public data needed to study systemic risks, misinformation, and platform harms.

- Proportionate Penalty with Teeth: €120 million represents first significant enforcement under DSA; DSA allows fines up to 6% of global annual revenue for serious violations—establishing precedent that regulatory obligations are not optional.

- Geopolitical Fallout: Elon Musk called for EU abolition; Trump administration criticized the fine as “overreach”; Tesla CEO threatened retaliation—escalating US-EU tech tensions and raising questions about regulatory extraterritoriality and corporate power.

Understanding the Three Violations

Violation 1: The Deceptive Blue Checkmark

Before Elon Musk’s acquisition in October 2022, Twitter’s blue checkmark was a trust signal—verification that an account belonged to who it claimed to represent.

Government officials, celebrities, journalists, academics—they were verified. Users could distinguish authentic voices from impersonators. The checkmark meant: “We’ve verified this person’s identity.”

After Musk: The blue checkmark became purchasable. X Premium ($8/month in the US,₹700/month in India). Anyone paying got the badge without meaningful verification.

The Problem: Users couldn’t tell if an account was authentic or purchased verification. A scammer could pay for a checkmark, impersonate a government official, and defraud citizens. A cryptocurrency fraudster could appear legitimate. A bot farm could masquerade as real people.

The EU’s Finding: This violates the Digital Services Act’s prohibition on “deceptive design practices”—interface features that mislead users or manipulate their choices.

Henna Virkkunen, EU’s Executive Vice-President for Tech Sovereignty, stated: “Deceiving users with blue checkmarks, obscuring information on ads and shutting out researchers have no place online in the EU. The DSA protects users.”

X’s defense: It’s a product feature, clearly marketed as a subscription. Users should exercise their own judgment.

The EU’s counter: The DSA doesn’t require user verification; it prohibits falsely claiming users have been verified when they haven’t. That’s deception regardless of disclaimers. digital-strategy.ec.europa

Violation 2: Non-Transparent Advertising Repository

The DSA mandates that very large platforms (45+ million monthly users) maintain a public, searchable repository of advertisements showing:

- What the ad says (content and topic)

- Who is paying for it (advertiser identity)

- Targeting parameters (audience demographics, interests)

- When it was displayed

- Any associated risks

Why this matters: Political interference, election manipulation, and foreign disinformation often exploit opaque advertising. If you can’t see who’s paying for political ads or what audiences they’re targeting, manipulation becomes invisible.

X’s failure: The advertising repository lacks accessible information about ad content, advertiser identity, and topic. X imposes “excessive delays in processing” requests for access. Design features and access barriers “undermine the purpose of ad repositories.”

Consequence: Researchers and civil society cannot detect political interference campaigns, coordinated influence operations, or fake advertisements. Public trust in electoral integrity erodes.

Violation 3: Restricted Researcher Data Access

The DSA requires platforms provide researchers access to public data to study systemic risks: disinformation spread, algorithmic amplification, extremism radicalization, recommendation system harms.

Why this matters: Independent research is essential for democratic oversight. Researchers from universities and civil society organizations need to understand how platforms amplify content, what algorithms recommend, and whether those systems enable harm.

X’s obstruction: X’s terms of service prohibit eligible researchers from independently accessing public data (including through scraping). Additional barriers and procedural obstacles “effectively undermine research into several systemic risks in the European Union.”

Impact: The only perspective on X’s systemic risks comes from X itself—a company with obvious incentives to minimize harm claims.

The Geopolitical Explosion

Musk’s Response: Abolish the EU

Within 24 hours of the fine, Elon Musk posted on X:

“The EU should be abolished and sovereignty returned to individual countries”

He characterized the fine as government overreach, called for EU dissolution, and hinted at retaliation.

This wasn’t measured corporate disagreement. It was explicit challenge to European democratic institutions and rule of law.

Trump Administration’s Assault

The Trump administration echoed Musk’s complaint:

- Described the fine as “nasty”

- Called EU regulations “overreach” and “targeted American innovation”

- Warned of retaliation against EU tech regulations

- Framed it as protectionist rather than legitimate governance

Andrew Puzder (Trump advisor) called the fine an attack on “American innovation” and claimed it was “targeting US companies abroad.”

The subtext: The US sees EU regulation not as democratic accountability but as competitive threat to American tech dominance.

What This Reveals

The firestorm around X’s fine exposes the deeper reality of tech governance: it’s not primarily about consumer protection or democratic values—it’s about power, sovereignty, and control over the digital economy.

The US wants regulatory light-touch enabling American companies to dominate globally. The EU wants regulatory strictness protecting European citizens and asserting digital sovereignty against US tech giants. China wants state control over digital infrastructure.

India is caught in the middle.

What the Fine Actually Means

Breaking Down €120 Million

€120 million seems large until you contextualize:

- Relative to X’s value: X (Musk-owned, private) is valued between $15-20 billion. €120 million is 0.6-0.8% of valuation—an annoying fine, not existential threat.

- Relative to DSA penalties available: DSA permits fines up to 6% of global annual revenue. X paying only 0.6-0.8% of company value suggests the Commission showed relative restraint.

- Precedent-setting power: €120 million is first enforced penalty under DSA. The significance isn’t financial—it’s demonstrating that DSA obligations are enforceable.

What X Must Do Now

The Commission issued a non-compliance decision requiring:

- 60 days: Submit specific measures to address deceptive blue checkmark system

- 90 days: Submit comprehensive action plan addressing advertising transparency and researcher data access

- Failure to comply: Risk periodic penalty payments and escalated enforcement

X can appeal, request extensions, or promise “good faith” corrections. But the Commission’s message is clear: Compliance is not optional.

Why This Fine Matters More Than Its Magnitude

- Enforces Democratic Standards: The EU is saying platforms can’t deceive users to profit. Checkmarks signal verification or they don’t—no middle ground.

- Democratizes Oversight: Researchers need data access. No company gets to be sole arbiter of its own harms.

- Sets Global Precedent: Other regulators (India, UK, Brazil, Singapore) now see that comprehensive digital regulation is enforceable.

- Signals Willingness: The EU has suffered years of tech CEO dismissal (“move fast and break things”). This fine says “We’re serious. Obey our law or face consequences.”

Global Governance Models

The Three Regulatory Models

| Dimension | EU (DSA) | USA (Section 230) | China | India (Emerging) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | User protection through transparency | Free expression through immunity | State control through surveillance | Hybrid: Innovation + Protection |

| Platform Scale Thresholds | VLOPs (45M+ users) subject to strict rules | No scale-based differentiation | All platforms subject to state oversight | SSMIs (5M+ users) defined |

| Content Moderation | Proactive with DSA compliance | Largely platform discretion | State-mandated censorship | Government notification-based |

| Researcher Data Access | Mandatory | No requirement | Controlled by government | Not yet mandated |

| Advertising Transparency | Public searchable repository required | No requirement | State monitoring | Proposed under review |

| Potential Penalties | Up to 6% global revenue | Minimal/none | Criminal/business termination | Under development |

| Geopolitical Stance | Digital sovereignty + user protection | Tech industry primacy | State control/surveillance | Strategic autonomy |

Strengths and Weaknesses of Each Approach

EU Model Strengths:

- Comprehensive, clear obligations

- Actual enforcement mechanisms

- Independent oversight through researchers

- Harmonized across 27 democracies

EU Model Weaknesses:

- Complex compliance burden (favors large incumbents)

- Risk of regulatory overreach

- Tech company hostility

- Geopolitical tensions

US Model Strengths:

- Enabled internet innovation and growth

- Flexible, market-driven

- Protects free expression

US Model Weaknesses:

- Insufficient accountability for platform harms

- Platforms exploit immunity for profit

- Reactive rather than proactive

- Inconsistent state-level regulations

China Model Strengths:

- Effective control

- No corporate resistance

China Model Weaknesses:

- Authoritarianism, censorship

- No user rights or democratic values

- Repression of dissent

- Incompatible with democratic societies

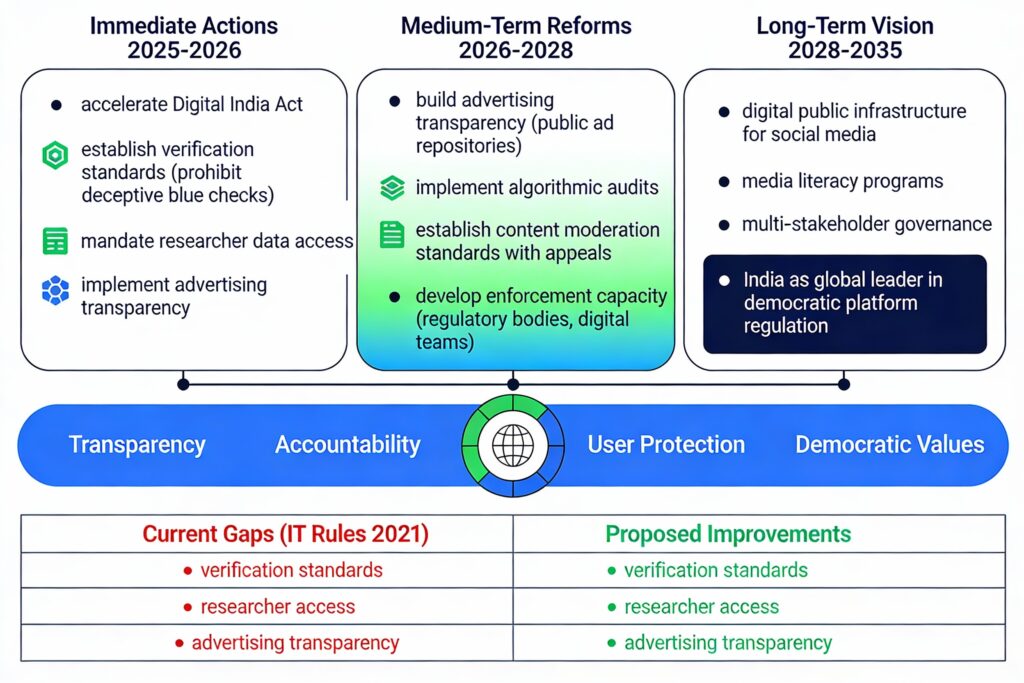

What India Should Learn

India should avoid copying any single model wholesale. Instead, adopt a hybrid approach:

- EU’s transparency and researcher access obligations (essential for democracy)

- US’s emphasis on expression and innovation (essential for development)

- Neither China’s authoritarianism nor blanket immunity

India’s path: Strong democratic governance with accountability, but not state censorship.

India’s Current Framework and Gaps

Current Landscape

Information Technology Act, 2000: Outdated; predates social media.

IT (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021: Defines content moderation, intermediary liability, grievance redressal; Section 79 provides safe harbor if platforms comply with due diligence.

2025 Amendments to IT Rules: Focus on synthetic media (deepfakes), AI-generated content labeling, tightened oversight of government removal orders (requiring reasoned intimations from senior officials).

Digital India Act (Proposed): Comprehensive update seeking to modernize digital governance framework.

Supreme Court Directions (August 2025): Directed government (with National Broadcasters and Digital Association) to frame guidelines for influencers/podcasters, emphasizing proportionate consequences, sensitization, and accountability.

Key Gaps Compared to DSA

| Obligation | EU DSA | India (Current) | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verification System Standards | Prohibits deceptive design | Not addressed | India could adopt X scenario: paid verification system misleading users |

| Advertising Transparency | Public searchable repository with advertiser ID, targeting, content | No requirement | Political ads can be dark and opaque |

| Researcher Data Access | Mandatory API access | Not mandated | Academics can’t independently study platform harms |

| Scale-Based Obligations | Stricter rules for VLOPs (45M+ users) | SSMIs (5M+ users) defined but fewer obligations | Smaller platforms less accountable |

| Fine Structure | Up to 6% global revenue | Not clearly defined in IT Rules 2021 | Weak enforcement incentives |

| Independent Oversight | Researchers auditing platforms | Primarily government-based | No civil society or academic oversight equivalent |

India’s Path Forward—Policy Recommendations

Immediate Actions (2025-2026)

1. Digital India Act Incorporates DSA Lessons

- Define “Very Large Digital Platforms” (perhaps 50M+ Indian users)

- Stricter transparency obligations for VLDPs

- Mandatory advertising repository showing advertiser identity, spend, targeting

- Researcher data access mandates with privacy safeguards

2. Verification System Standards

- Prohibit purchasable “verified” badges without meaningful authentication

- If platforms offer verification, publish transparent criteria

- Multiple authentication pathways (Aadhaar, government ID, institutional)

- Regular audits preventing verification system gaming

- Explicit prohibition on false claims of verification

3. Content Moderation Transparency

- Public reporting of content removals, appeals, suspension ratios

- DSA-style transparency database of removal decisions (with privacy protections)

- Clear, published policies explaining what content violates standards

- Mandatory appeals mechanism with human review for major decisions

Medium-Term Reforms (2026-2028)

1. Establish Independent Digital Regulator

- Similar to EU’s approach: dedicated authority overseeing platform compliance

- Staffed with technical experts, civil society representatives, academics

- Power to audit algorithms, content moderation, advertising systems

- Proportionate penalty authority (but not arbitrary state censorship)

2. Advertising Transparency System

- Elections Commission monitoring political advertising (2026 state elections opportunity)

- Public ad repository for all issue-based and political advertising

- Advertiser identity disclosure

- Real-time public access to ad spend and targeting

3. Researcher Data Access Framework

- API access for academic researchers studying misinformation, polarization, platform harms

- Privacy-preserving protocols protecting individual user data

- Government funding for independent AI/platform research

- Research outcomes published for public benefit

4. Capacity Building

- Recruiting technical staff for regulatory agencies

- Training on algorithm auditing, content moderation, platform risks

- International cooperation with EU, US regulators on best practices

Long-Term Vision (2028-2035)

1. Digital Public Infrastructure

- Open protocols supporting federated, interoperable social networks (like email)

- Government-run or publicly-owned social media platform option

- Supporting Indian platforms (Koo, ShareChat, ONDC) to compete globally

- Data portability enabling users to move across platforms

2. Media Literacy and Democratic Resilience

- School curriculum on platform mechanics, algorithmic amplification, misinformation detection

- Public awareness campaigns in 22 Indian languages

- Training community leaders, journalists, educators

- Digital citizenship education starting in primary school

3. Multi-Stakeholder Governance

- Advisory councils with civil society, academia, industry, users

- Participatory rulemaking on major policy decisions

- Independent oversight bodies (like Press Council model for digital)

- Periodic review and updating based on evidence

4. Global Leadership

- India as model for responsible platform governance for Global South

- Technology sharing and capacity building with developing countries

- Active participation in UN, G20, multilateral forums on AI/platform governance

- Mediating between US and EU regulatory models

Balancing Act—Critical Tensions

Innovation vs. Safety

Risk: Heavy regulation stifles startups and innovation.

Mitigation: Proportionate rules scaled to platform size; regulatory sandboxes for experimentation; sunset clauses requiring periodic review; startup support programs.

Privacy vs. Accountability

Risk: Researcher data access compromises user privacy.

Mitigation: Privacy-preserving techniques (differential privacy, aggregation); anonymized datasets; legal agreements protecting data; oversight by independent boards.

Free Speech vs. Harm Prevention

Risk: Content moderation rules silence legitimate voices.

Mitigation: Transparent, narrow criteria; appeals mechanisms; judicial oversight; strong due process; avoiding vague terms like “public order.”

Sovereignty vs. Integration

Risk: Asserting control isolates India from global digital economy.

Mitigation: Standards-based interoperability; bilateral/multilateral agreements; reciprocal arrangements; participation in international standard-setting.

Conclusion: India’s Regulatory Moment

The EU’s €120 million fine on X represents a fundamental shift in digital governance: companies can no longer assume immunity or treat regulatory obligations as optional.

For India, this moment is strategic opportunity.

The opportunity: Develop a regulatory model balancing EU’s comprehensive protection with US’s innovation ethos, adapted to India’s democratic, diverse, digital-divided context.

The risk: Lag behind, let platforms exploit governance gaps, and watch Indian democracy degraded by unaccountable platforms.

India’s choices now—how it crafts the Digital India Act, implements transparency mandates, and establishes oversight capacity—will shape the next decade of digital democracy.

The X fine exemplifies 21st-century governance: technology outpacing law, platforms wielding quasi-governmental power, national sovereignty tensions with global platforms, and the necessity of integrated policy frameworks spanning legal, institutional, technical, and diplomatic domains.

+ There are no comments

Add yours