Key Highlights:

Transformative Initiatives: Union Budget 2025 introduced Bharatiya Bhasha Pustak Scheme for digital books in Indian languages, complementing ASMITA’s goal to create 22,000 books across 22 scheduled languages

Platform Integration: PM e-VIDYA unifies DIKSHA (495+ crore learning sessions), SWAYAM (10,000+ courses), 200 TV channels, and accessibility features for inclusive digital education

Persistent Divide: Only 37% of rural households have internet access versus 67% urban; 22% of rural schools have computer labs compared to 55% urban schools

Teacher Capacity Gap: Over 70% of rural teachers lack formal ICT training; only 33% of Indian teachers are comfortable using digital tools for instruction

SDG 4 Alignment: Digital initiatives advance inclusive education goals but India remains off-track in foundational literacy, teacher training, and education financing benchmarks

The Promise of Inclusive Learning in a Multilingual Nation

Education has always been the great equalizer, the ladder that lifts communities from poverty to prosperity. Yet for millions of Indian students, that ladder has rungs missing—particularly when it comes to language and access to quality learning materials. The Union Budget 2025’s announcement of the Bharatiya Bhasha Pustak Scheme signals a transformative shift toward digital, multilingual education that could rewrite India’s educational narrative.

This initiative promises to provide digital textbooks in Indian languages for school and higher education students, complementing the ambitious ASMITA project that aims to develop 22,000 books across 22 scheduled languages. Together, these programs represent India’s most comprehensive effort yet to democratize education through technology while honoring linguistic diversity.

Context: Why Digitalisation Matters for India’s Educational Ecosystem

The Socio-Economic Imperative

Education remains the most powerful catalyst for socio-economic development and national integration. India’s journey from 91.6% primary completion rates toward universal education demonstrates progress, yet significant challenges persist in ensuring equitable learning outcomes across regions, languages, and socio-economic strata. researchjournal

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 explicitly recognizes that education must develop not just cognitive capacities but also social, ethical, and emotional competencies. It emphasizes providing quality education to all students irrespective of their place of residence, with particular focus on historically marginalized and disadvantaged groups.

The Digital Divide Reality

India confronts a stark digital divide that threatens to widen educational inequalities. According to recent data, only 37% of rural households have internet access compared to 67% in urban areas. This disparity extends to educational infrastructure: merely 22% of rural schools have functional computer labs versus 55% of urban schools. amulyacharan

Ministry of Education data reveals that urban schools lead rural schools in internet connectivity by nearly 29 percentage points. This digital infrastructure gap severely limits rural students’ ability to access online learning resources that urban counterparts take for granted.

The socio-economic dimensions compound these challenges. Only 45% of rural households own smartphones compared to 74% in urban areas. For millions of families, the cost of devices and data connectivity remains prohibitive.

Government Initiatives: Building a Digital Learning Architecture

Bharatiya Bhasha Pustak Scheme

Announced in Union Budget 2025-26 by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, the Bharatiya Bhasha Pustak Scheme represents a landmark initiative to provide digital-form Indian language books for school and higher education.

The scheme aims to help students understand subjects better by offering study materials in regional languages, thereby bridging the language gap that has historically disadvantaged students from diverse linguistic backgrounds. While specific financial allocations are yet to be announced, the scheme will make digital textbooks and learning resources accessible through government-supported e-learning platforms like DIKSHA, e-PG Pathshala, and the National Digital Library of India. ijarsct.co

ASMITA Project

Launched in July 2024 by the Ministry of Education and University Grants Commission (UGC), ASMITA (Augmenting Study Materials in Indian Languages through Translation and Academic Writing) represents the content backbone for India’s multilingual education vision. educationworld

The project’s ambitious goal is to create 1,000 books in each of 22 scheduled languages within five years, totaling 22,000 books across various higher education disciplines. This encompasses both translation of existing academic content and encouragement of original writing in Indian languages.

Thirteen nodal universities have been identified to spearhead this effort, with member universities across regions participating. The UGC established a comprehensive Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) covering the entire process from author identification through manuscript review, plagiarism checking, designing, proofreading, and e-publication.

Complementing ASMITA, the ministry launched Bahubhasha Shabdakosh, a comprehensive multilingual dictionary developed by the Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL) in collaboration with the Bharatiya Bhasha Samiti. This resource standardizes terminology across diverse domains including IT, industry, research, and education.

PM e-VIDYA: Multi-Modal Digital Education

Launched on May 17, 2020, under the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyaan, PM e-VIDYA unifies all digital, online, and on-air education efforts to benefit nearly 25 crore school-going children across India.

The initiative encompasses multiple complementary platforms:

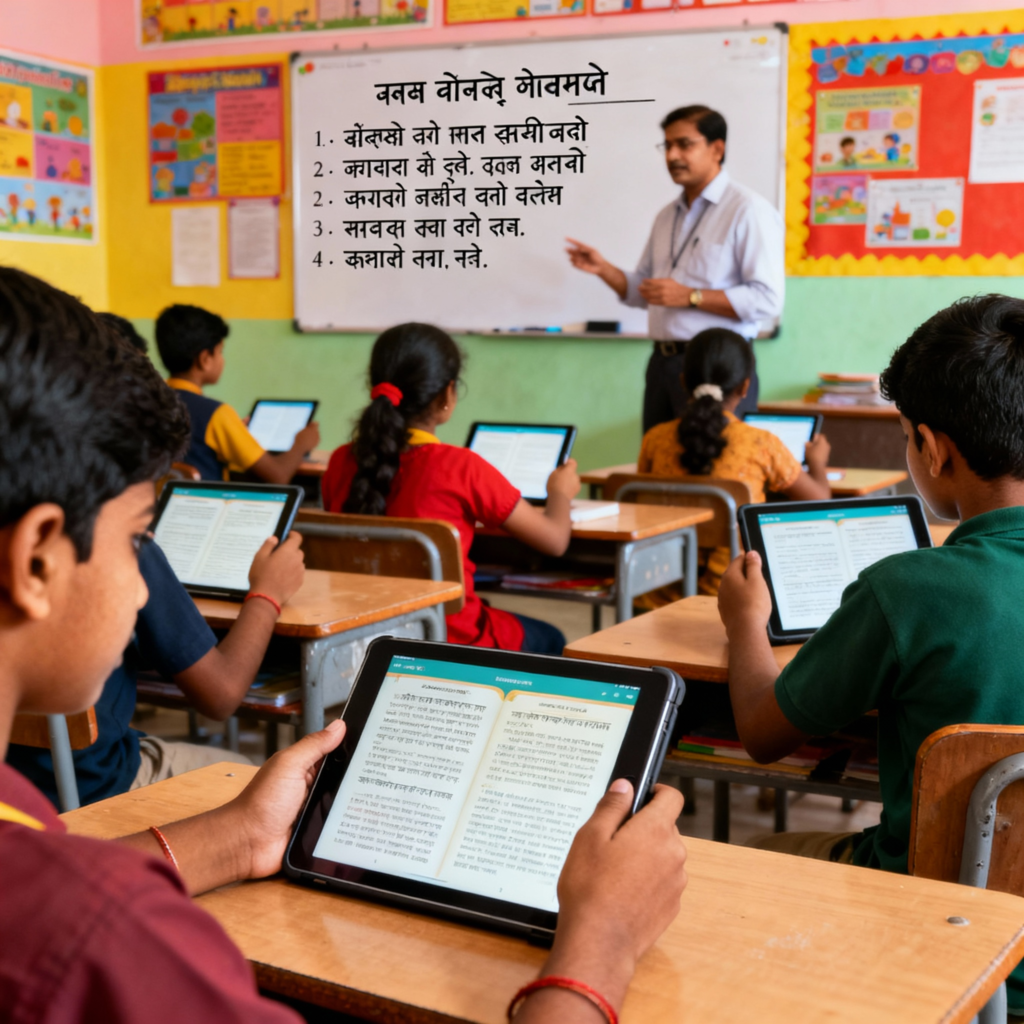

DIKSHA (Digital Infrastructure for Knowledge Sharing) serves as India’s national digital platform for school education—declared “One Nation, One Digital Platform” in 2020. Adopted by all 36 states and union territories, DIKSHA provides QR-coded Energized Textbooks for all grades, along with high-quality e-content in 36 Indian languages.

As of July 2022, DIKSHA recorded over 495 crore learning sessions, with more than 47 lakh teachers benefitting from professional development courses. The platform hosts 2,91,168 pieces of e-content and 6,477 QR-coded textbooks. Studies in rural Rajasthan found that 96% of teachers learned to use DIKSHA during the pandemic, using it for lesson plans, assessments, and improving teaching skills.

SWAYAM (Study Webs of Active-Learning for Young Aspiring Minds) offers higher education courses in MOOC format with credit transfer provisions. Currently, over 10,000 courses are available with 4.1 lakh students enrolled in NCERT courses. The platform also offers school courses for grades 9-12 via NIOS.

PM e-Vidya DTH TV Channels expanded from initially 12 channels to 200 channels, providing supplementary education in multiple Indian languages for classes 1-12 across states and union territories. A dedicated Channel 31 on DTH provides Indian Sign Language (ISL) training for hearing-impaired students, special educators, and parents.

Radio, Community Radio, and CBSE Podcast (Shiksha Vani) broadcast educational content to wider audiences, especially in areas with limited internet access.

Digitally Accessible Information System (DAISY) provides e-content specifically for visually and hearing-impaired students, including audiobooks, sign language videos, and talking books available on the NIOS website and YouTube.

Benefits of Digitalising Educational Books

Promoting Linguistic Diversity and Inclusivity

The most transformative benefit of digital book initiatives lies in their potential to honor India’s extraordinary linguistic diversity. The NEP 2020 emphasizes mother-tongue-based instruction at the foundational level, recognizing that children learn better when taught in their native language.

Research consistently demonstrates that students receiving instruction in their mother tongue during early years show superior learning outcomes, better cognitive development, and stronger cultural identity. The three-language formula advocated by NEP 2020 allows educational institutions to offer local mother language alongside regional language, Hindi, and English.

Digital platforms enable this multilingual approach at scale. DIKSHA’s availability in 36 languages ensures students can access content in familiar linguistic frameworks. The ASMITA project’s focus on creating original academic content in 22 scheduled languages addresses the historical neglect of regional languages in higher education.

Bridging Urban-Rural Divides

While the digital divide remains a challenge, digital textbooks offer pathways to bridge geographical disparities. Unlike physical books requiring complex distribution logistics, digital content can reach remote areas through mobile networks, community digital centers, and government schools equipped with basic infrastructure.

The BharatNet project’s expansion to provide broadband connectivity to all government secondary schools in rural areas promises to enhance accessibility. Combined with the establishment of 50,000 Atal Tinkering Labs in government schools over five years, these infrastructure investments create an ecosystem where digital books can genuinely democratize access.

Mobile learning vans and community Wi-Fi networks established through public-private partnerships extend reach to areas where home internet access remains limited. This multi-modal approach ensures that digital education doesn’t become an exclusively urban phenomenon.

Integration with NEP 2020’s Vision

Digital textbooks align perfectly with NEP 2020’s emphasis on critical thinking, competence development, and self-learning. Interactive digital content enables students to learn at their own pace, revisit concepts, and access supplementary materials beyond static textbook pages.

The policy’s focus on holistic and multidisciplinary education finds expression through digital platforms that integrate diverse subjects and perspectives. DIKSHA’s MOOC courses and SWAYAM’s higher education offerings allow students to explore subjects beyond their core curriculum.

Digital books facilitate continuous assessment through embedded quizzes and interactive exercises, supporting the NEP 2020’s shift from rote learning to conceptual understanding. The ability to update content rapidly ensures curricula remain relevant to evolving knowledge and societal needs.

Enhanced Accessibility for Students with Disabilities

Digital formats dramatically improve accessibility for students with disabilities. The Digitally Accessible Information System (DAISY) provides audiobooks, talking books, and sign language videos specifically designed for visually and hearing-impaired learners.

Text-to-speech functionalities, adjustable font sizes, high-contrast modes, and screen reader compatibility make digital textbooks accessible to students with various disabilities. This inclusive design aligns with SDG 4’s emphasis on ensuring quality education for all, including persons with disabilities.

Challenges: The Obstacles to Digital Education Equity

Digital Infrastructure Gaps

Despite progress, fundamental infrastructure challenges persist. Internet connectivity, reliable electricity, and device availability remain acute problems in rural and remote areas.

Studies reveal that 40% of teachers lack smartphones, and 55% of rural schools lack internet connectivity. UNESCO data indicates that over 70% of rural government school teachers lack formal ICT training. Frequent power cuts and unreliable electricity supply undermine the viability of digital learning even where other resources exist.

DIKSHA usage data shows regional variations reflecting infrastructure disparities. While Tamil Nadu achieved 90% adoption, Nagaland recorded only 60%. Andhra Pradesh ranked third nationally with 90 lakh learning sessions, highlighting how states with better digital infrastructure achieve superior outcomes.

Teacher Training and Digital Literacy

The success of digital education fundamentally depends on teacher capacity. Many educators, particularly in rural government schools, have limited exposure to information and communication technology and receive inadequate formal training in digital pedagogy.

This skill gap undermines teachers’ ability to integrate technology meaningfully into teaching practices. High workloads and lack of continuous professional development opportunities lead to reluctance or inability to adopt new methodologies.

Research indicates that only 33% of Indian teachers are comfortable using digital tools for teaching. Interface issues like login errors and OTP delays on platforms like DIKSHA further frustrate educators attempting to embrace digital resources.

The NEP 2020 calls for transforming the teacher education system into multidisciplinary colleges with four-year integrated B.Ed. programs and developing National Professional Standards for Teachers (NPST). However, translating these policy visions into widespread teacher capacity remains a substantial challenge.

Socio-Economic Disparities

Digital access correlates strongly with socio-economic status. Students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds often lack personal digital devices or supportive home environments for remote learning.

Cultural norms and safety concerns restrict girls’ access to smartphones and the internet, creating gendered digital divides. Studies show boys in many rural communities have greater freedom and encouragement to engage with digital technology, while girls face constraints due to traditional expectations and household responsibilities.

The National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) data reveals that only 24% of rural households have internet access compared to 66% in urban areas. This disparity means digital initiatives risk benefiting already-privileged urban students while marginalizing rural learners.

Content Standardisation and Quality Control

Creating high-quality educational content across 22 languages presents formidable challenges. Ensuring consistent academic rigor, accurate translation, and cultural appropriateness requires extensive quality control mechanisms.

The ASMITA project’s SOP addresses these concerns through multi-stage review processes including plagiarism checks, expert evaluation, and editing. However, scaling this quality assurance across 22,000 books demands substantial coordination and expertise.

Terminology standardization across languages remains complex, necessitating resources like Bahubhasha Shabdakosh to ensure consistent usage of technical and academic terms. Balancing fidelity to original texts with culturally appropriate adaptations requires linguistic expertise and pedagogical insight.

Critical Analysis: A Perspective

Alignment with Sustainable Development Goal 4

SDG 4 commits to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”. India’s digital book initiatives directly advance multiple SDG 4 targets.

Target 4.1 focuses on ensuring all girls and boys complete free, equitable, and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant learning outcomes. Digital textbooks in regional languages enhance comprehension and retention, improving learning outcomes particularly for students whose mother tongue differs from the medium of instruction.

Target 4.5 emphasizes eliminating gender disparities and ensuring equal access to education for vulnerable groups including persons with disabilities and indigenous peoples. Digital content with accessibility features and multilingual availability supports inclusive education across diverse populations.

Target 4.c calls for substantially increasing the supply of qualified teachers, including through international cooperation for teacher training. Platforms like DIKSHA offering continuous professional development courses for teachers align with this target, though gaps in teacher digital literacy remain.

India’s 2025 SDG 4 scorecard reveals mixed progress. While the country has nearly universalized primary and lower secondary education and shows gains in gender parity and internet connectivity, it remains off-track in foundational literacy, teacher training, and financing. The benchmark for reading proficiency at the end of primary education is 56%, but actual achievement falls substantially lower. UNESCO notes that India is “off track by 11 percentage points” from achieving minimum reading proficiency benchmarks.

Fiscal Allocation and Implementation Assessment

Budget allocations signal government priorities. The Union Budget 2025-26 announced several education-focused initiatives including the Bharatiya Bhasha Pustak Scheme, Rs 500 crore for a Centre of Excellence in AI for Education, Rs 20,000 crore for private sector-driven Research, Development and Innovation, and infrastructure expansion in IITs.

However, specific allocations for the Bharatiya Bhasha Pustak Scheme remain undisclosed. The Electronics Component Manufacturing Scheme received Rs 22,919 crore, aiming to attract Rs 59,350 crore in investments and create 91,600 direct jobs. These investments in digital infrastructure support the ecosystem necessary for digital education.

India’s public education expenditure has declined from 13.8% to 12.7% of total public expenditure, moving further from the minimum SDG 4 benchmark of 15%. This underscores the gap between policy intent and fiscal commitment.

State-level variations in budget effectiveness are significant. Kerala and Tamil Nadu lead most states in education spending efficiency, while challenges like official ineptitude, exploitation, and inequitable resource allocation persist elsewhere. Decentralized budgeting, improved transparency, and targeted investments in teacher training and infrastructure are recommended.

Stakeholder Impact Analysis

Students represent the primary beneficiaries, gaining access to affordable, multilingual learning materials that improve comprehension and engagement. However, those lacking devices, connectivity, or digital literacy risk exclusion, potentially widening inequality.

Teachers benefit from professional development resources on platforms like DIKSHA, enabling skill enhancement and pedagogical innovation. Yet inadequate training, high workloads, and interface challenges create barriers to effective utilization.

State governments gain tools to expand educational access and improve learning outcomes, particularly for underserved populations. Implementation success varies by state capacity, infrastructure, and political will.

EdTech firms find opportunities in content creation, platform development, and distribution partnerships. However, data privacy regulations under the Digital Data Protection Act 2023 impose compliance obligations, particularly regarding children’s data.

The publishing industry faces disruption as digital books challenge traditional print business models. Some publishers may pivot to digital content creation, while others struggle to adapt.

Ethical Considerations: Privacy and Data Protection

The proliferation of digital education platforms raises critical privacy concerns, especially regarding children under 18.

The Digital Data Protection Act 2023 requires “verifiable parental consent” for collecting and processing children’s personal data. The Act prohibits tracking, behavioral monitoring, and targeted advertising directed at children.

EdTech platforms collect vast amounts of student data including names, school affiliations, academic performance, device identifiers, and behavioral insights. Without robust governance frameworks, some platforms adopt opaque privacy policies, fail to obtain meaningful parental consent, and may share or monetize data without clear justification.

A Human Rights Watch report found that 89% of EdTech products globally engage in predatory data practices, putting children’s data at risk. In India, children spend an average of 3-5 hours daily on the internet, making them vulnerable to data collection, inappropriate content, and cyberbullying.

The absence of sector-specific standards tailored for EdTech creates regulatory gaps. Experts recommend mandating data minimization, purpose limitation, storage limitation, and child-centric privacy principles including default opt-outs and child-friendly interfaces.

Case Studies and Comparative Insights

DIKSHA Implementation: Successes and Challenges

DIKSHA’s adoption across all Indian states and union territories demonstrates scalability. Rajasthan ranked first nationally with 1 crore learning sessions, followed by Uttar Pradesh with 95 lakh sessions and Andhra Pradesh with 90 lakh sessions.

A study in rural Rajasthan during COVID-19 found that 96% of teachers learned to use DIKSHA and used it for lesson plans, assessments, question banks, and improving teaching skills. 95% of students used DIKSHA to access digital textbooks and interactive worksheets, helping bridge learning gaps during school closures.

However, challenges related to internet connectivity, interruptions, and digital literacy persist. A national study found that 35.8% accessed DIKSHA weekly and 14% daily, while 24.6% used it rarely and 15.1% never used it. Teachers with 1-3 years of experience found professional development content most useful, while engagement varied among others.

International Comparisons

Finland’s education system emphasizes teacher autonomy, continuous professional development, and equitable resource allocation. Teachers receive extensive pre-service training and ongoing support, enabling effective technology integration.

Japan combines traditional pedagogical strengths with strategic technology adoption, focusing on improving learning outcomes rather than technology for its own sake. Government investments in infrastructure ensure schools have necessary resources.

Nigeria and India face similar challenges including large populations, socio-economic disparities, and infrastructure gaps. Both countries show progress in expanding access but struggle with quality, particularly in foundational literacy and teacher training.

Policy Recommendations: Building an Inclusive Digital Future

Strengthening Digital Infrastructure

Accelerating BharatNet rollout to provide broadband connectivity to all government secondary schools and primary health centers in rural areas must be a priority. Expanding mobile network coverage in remote regions through public-private partnerships can bridge connectivity gaps.

Establishing community digital centers equipped with computers, tablets, and reliable internet access provides shared infrastructure where individual device ownership remains limited. Solar power solutions can address electricity reliability issues in areas with unstable grid supply.

Investing in Teacher Training

Continuous professional development programs specifically focused on digital pedagogy should be mandatory for all teachers. Training must go beyond basic ICT skills to encompass effective online teaching methods, content creation, student engagement strategies, and assessment techniques.

DIKSHA’s NISHTHA (National Initiative for School Heads’ and Teachers’ Holistic Advancement) courses provide a foundation, having benefited more than 47 lakh teachers. However, expanding reach, improving completion rates, and ensuring application of learned skills in classrooms require systematic institutional support.

Incentivizing teachers who demonstrate digital proficiency through career advancement opportunities and recognition can accelerate adoption. Reducing administrative burdens allows teachers time to develop digital competencies and integrate technology meaningfully into instruction.

Fostering Public-Private Partnerships

Collaborations between government, EdTech firms, telecommunications companies, and educational institutions can drive innovation in content creation, translation, and distribution.

Private sector expertise in user experience design, content delivery platforms, and adaptive learning technologies complements government’s reach and legitimacy. However, partnerships must be structured with clear data governance frameworks ensuring children’s privacy protection.

Industry-academia partnerships can support the ASMITA project’s goal of creating 22,000 books in 22 languages by leveraging translation technologies, subject matter expertise, and publishing capabilities.

Encouraging Feedback and Evaluation

Establishing robust monitoring and evaluation systems enables course correction and continuous improvement. Regular assessments of student learning outcomes, platform usage patterns, content quality, and stakeholder satisfaction should inform policy adjustments.

Creating systematic mechanisms for teachers, students, and parents to provide feedback on digital platforms ensures user perspectives shape development. Addressing common pain points like login errors, OTP delays, and interface complexity improves user experience and adoption rates.

State-level comparative analysis highlighting best practices and challenges facilitates peer learning. Kerala and Tamil Nadu’s success in education spending efficiency offers lessons for other states.

Conclusion: From Vision to Transformation

India stands at a pivotal juncture in its educational journey. The Bharatiya Bhasha Pustak Scheme, ASMITA project, and PM e-VIDYA represent more than policy announcements—they embody a vision of education that honors linguistic diversity, leverages technology for inclusion, and recognizes learning as a fundamental right transcending geographical and socio-economic boundaries.

Yet vision alone cannot transform systems. The stark disparities in digital infrastructure, teacher capacity, and resource allocation demand urgent, sustained attention. The promise of digital education risks remaining unfulfilled if we allow technology to become another privilege of the urban elite rather than an equalizer for marginalized communities.

Success requires more than fiscal allocations—it demands political will, administrative efficiency, and genuine commitment to leaving no learner behind. It requires viewing teachers not as obstacles to change but as partners in transformation, deserving of training, support, and respect.

As we digitalize textbooks, we must also digitalize our mindsets—recognizing that education in a child’s mother tongue is not a concession but a cognitive advantage; that rural students deserve the same quality resources as their urban counterparts; that disabilities should not determine destinies.

India’s 140 crore people represent an ocean of potential. Digital education initiatives offer vessels to navigate toward that potential—but only if we ensure those vessels reach every shore, not just the well-connected harbors.

What are your thoughts on India’s digital education push? Will digital textbooks truly bridge our educational divides, or risk widening them? Share your perspectives, experiences, and ideas in the comments below. Let’s build a conversation about the future of learning in our nation!

+ There are no comments

Add yours