Key Highlights

- 76.3% of Indian households have broadband internet, yet only 20% of rural and 40% of urban citizens can send emails, revealing a massive skills gap beyond mere access

- BharatNet has connected 2.14 lakh gram panchayats but last-mile connectivity remains incomplete, with Wi-Fi hotspots in less than 50% of covered panchayats

- Stark inequalities persist: General category households (84.1% broadband) vs. ST households (64.8%); poorest 71.6% lack broadband vs. richest 1.9%

- Gender gap is alarming: Only 33.3% women ever used internet vs. 57.1% men (NFHS 2019-21); women 40-56% less likely to use mobile internet

- Kerala High Court (2019) declared internet access as fundamental right under Article 21, forming part of right to education and privacy

India’s Digital Paradox

India stands at a remarkable crossroads in its digital journey. On paper, the numbers look impressive: 76.3% of households have broadband internet access, positioning the country as a rapidly digitalizing economy. The government proudly touts 20+ billion UPI transactions monthly and a thriving digital payments ecosystem.

Yet scratch beneath the surface, and a troubling reality emerges: Only 20% of rural citizens and 40% of urban residents can send or receive emails. This isn’t just a minor discrepancy—it’s evidence of a multi-layered digital divide that transcends simple connectivity metrics.

This paradox demands urgent attention. It touches upon fundamental questions of social justice, inclusive development, educational equity, and constitutional rights. As India races toward becoming a digital superpower, millions risk being left behind—creating what experts call the “new digital frontier of inequality”.

The landmark Comprehensive Annual Modular Survey (CAMS) 2022-23 by the National Sample Survey Office provides the first large-scale assessment of India’s digital landscape at household and individual levels, revealing uncomfortable truths about who truly benefits from digital transformation.

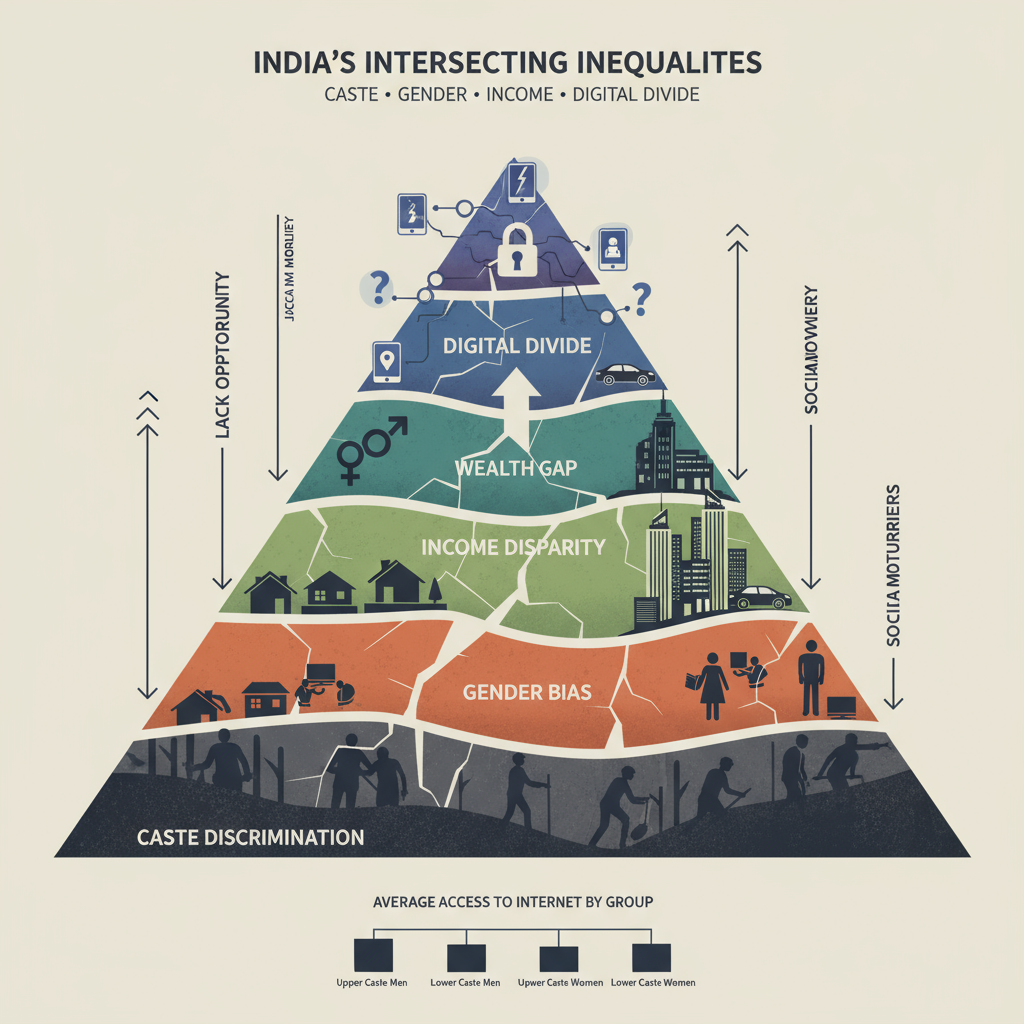

Understanding India’s Multi-Layered Digital Divide

Three Levels of Digital Exclusion

The digital divide is far more complex than simple internet access. Research identifies three distinct levels: arvix

First-level divide: Access to devices (computers, smartphones) and internet connectivity—the physical infrastructure layer.

Second-level divide: Skills to meaningfully use digital technologies—emailing, online banking, information searching—the functional capability layer.

Third-level divide: Quality, reliability, and tangible outcomes from digital access—the value realization layer.

CAMS 2022-23: The Wake-Up Call

The National Sample Survey Office’s CAMS survey (July 2022-June 2023) covering 3.02 lakh households and 12.99 lakh individuals provides unprecedented insights:

Broadband Penetration:

- National average: 76.3% households have broadband

- Urban areas: 86.5% vs. Rural areas: 71.2%

- Leading states (>90%): Delhi, Goa, Mizoram, Manipur, Sikkim, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh

- Lagging states: West Bengal (69.3%), Andhra Pradesh (66.5%), Odisha (65.3%), Arunachal Pradesh (60.2%)

The Skills Gap:

- Email capability: Only 20% rural, 40% urban can send/receive emails

- Online banking: Just 37.8% of population aged 15+ can perform transactions

- Over 55% Indians have broadband but only 20% can use internet meaningfully

This reveals the critical insight: Access ≠ Usage ≠ Empowerment.

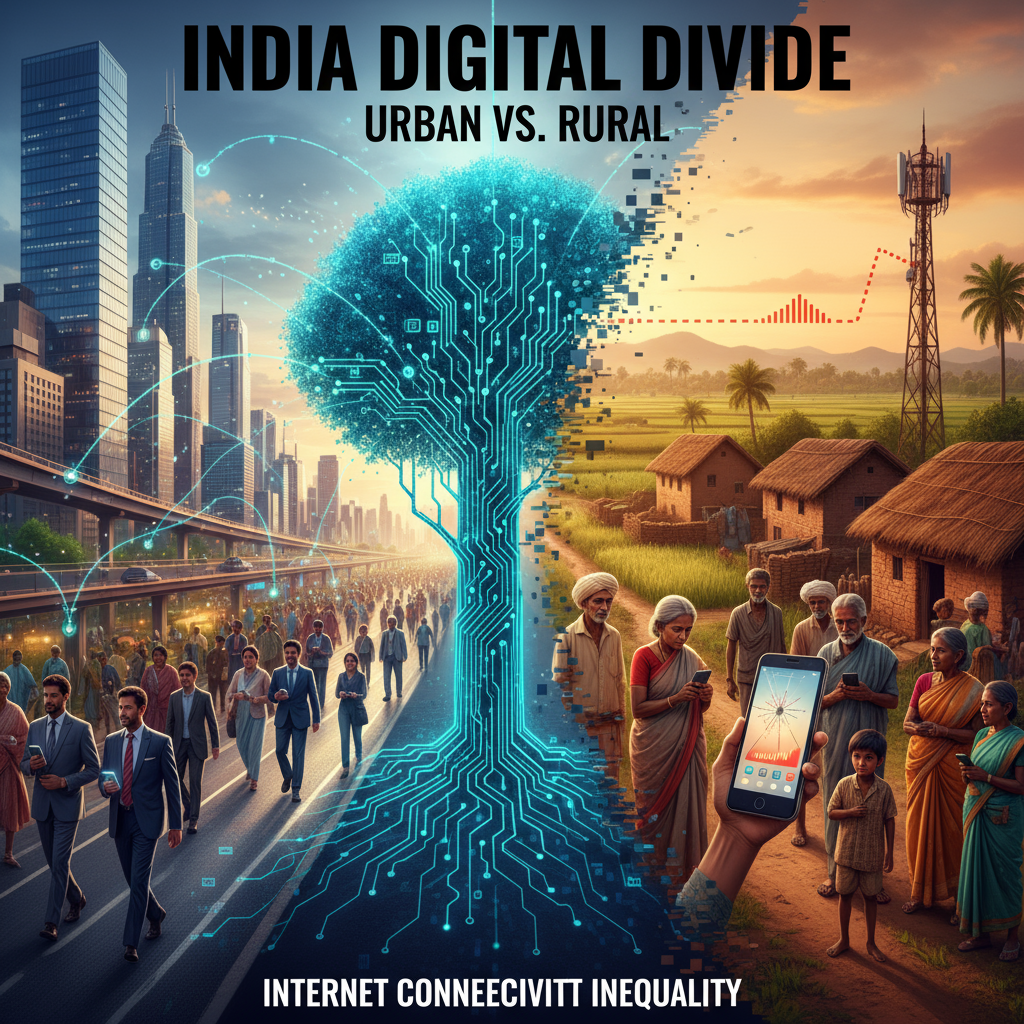

Geographic Divide: The Urban-Rural Chasm

Connectivity Disparities

The urban-rural gap remains stark despite infrastructure investments:

Internet Penetration:

- Rural India: 31% vs. Urban India: 67% active internet users (India Inequality Report 2022)

- Alternative data: Rural 14% vs. Urban 59% (NSSO)

- Only 24% of rural households have internet access compared to 66% in cities

Infrastructure Quality:

- Fiber-optic access: Only 7.2% households nationally; rural share mere 3.2%

- Home internet: Urban 15.3% fiber vs. Rural 3.8%

- Twice as many rural households (16.7%) lack internet vs. urban (8.4%)

BharatNet: Promise vs. Reality

BharatNet, launched in October 2011 as the world’s largest rural broadband connectivity program, aims to connect all 2.5 lakh gram panchayats:

Achievements:

- 2,14,283 Gram Panchayats connected (against target of 2,22,343 in Phase I & II)

- 6,92,299 km of Optical Fiber Cable laid

- 11,60,367 FTTH connections commissioned

- 1,04,574 Wi-Fi hotspots installed

- Affordable broadband starting at ₹99/month

Critical Gaps:

- Village office connected but homes, schools, clinics unreached—the last-mile challenge

- Wi-Fi hotspots in less than 50% of covered panchayats

- 8,060 GPs short of Phase I & II targets

- Multiple agencies (BBNL, BSNL, CSC-SPV, state govts) causing coordination delays

- Sustainability concerns: Prolonged reliance on government funds

As one researcher aptly put it: “Built digital highway but people don’t know how to drive on it”—infrastructure exists but awareness, devices, and usable content remain lacking.

Socio-Economic Dimensions: The Caste-Class-Gender Nexus

Caste-Based Digital Exclusion

India’s ancient social hierarchies replicate themselves in the digital sphere: idronline

First-Level Access Divide:

- General category: 84.1% broadband access

- OBCs: 77.5%

- Scheduled Castes (SCs): 69.1%

- Scheduled Tribes (STs): 64.8%

Second-Level Skills Divide:

- Only 6% of SC and ST individuals have computers at home vs. 20% among other castes

- Internet access: 14.1% STs vs. 41.1% higher castes

- Computer literacy gap: 87.5% explained by differences in covariates (education, income, urban residence)

Infrastructure Gaps:

- 8% of ST households offline due to infrastructure deficits—nearly four times the rate of upper-caste households (2.1%)

- Upper-caste rural households 2.5 times more likely to have optical fiber connectivity than SC/ST households

The research conclusion is stark: “Class location plays an underlying role in propagating digital divide”—caste determines not just social status but digital destiny.

Income-Based Inequality

The correlation between wealth and digital access is overwhelming:

Broadband Access by Income Decile:

- Poorest 10%: 71.6% households lack broadband

- Richest 10%: Only 1.9% lack broadband

- Even second-lowest decile shows 56.2% connectivity—demonstrating sharp improvement across income bands

Device Ownership:

- Computer access: Poorest 20%: 2.7% vs. Richest 20%: 27.6%

- Internet access: Poorest 20%: 8.9% vs. Richest 20%: 50.5%

Affordability Barriers:

- 40% of mobile subscribers don’t have smartphones

- 70% of population has poor or no connectivity to digital services

- Cost of devices and data plans prohibitive for low-income households

Gender Digital Divide: Structural Patriarchy in Digital Space

Access Gap

The gender dimension of India’s digital divide is deeply troubling:

Internet Usage (NFHS 2019-21):

- Women: 33.3% ever used internet

- Men: 57.1% ever used internet

- Gender gap: Women constitute only one-third of internet users

Urban-Rural Breakdown:

Mobile Ownership and Internet:

- Women 11% less likely to own mobile phones (GSMA 2024)

- Women 40-56% less likely to use mobile internet

- 61% men owned mobile phones (2021) vs. 31% women

Structural Barriers

Lack of Access:

- Low infrastructure and smartphone penetration compounded by gender inequality

- Patriarchal norms restricting women’s access to devices

- Restrictions in private/public space extending to digital space

Digital Illiteracy:

- 59% women aged 15-49 not completed 10+ years schooling (NFHS); 66% in rural areas

- Functional literacy inequality reducing ability to optimally use smartphones

Cyber Safety Concerns:

- Lower digital literacy making women vulnerable to online harassment, cyberbullying, cyberstalking

- Fear of digital risks restricting technology usage, widening divide

Rural Women’s Reality:

- Only 25.3% of rural General category women use mobile phones independently

- Percentage even lower among SC/ST women

- 94% rural households own mobiles but usage skewed by gender

Asia-Pacific’s Worst Gender Gap

India fares worst in Asia-Pacific with widest gender gap of 40.4%—a damning indictment of persistent gender inequality in the digital age.

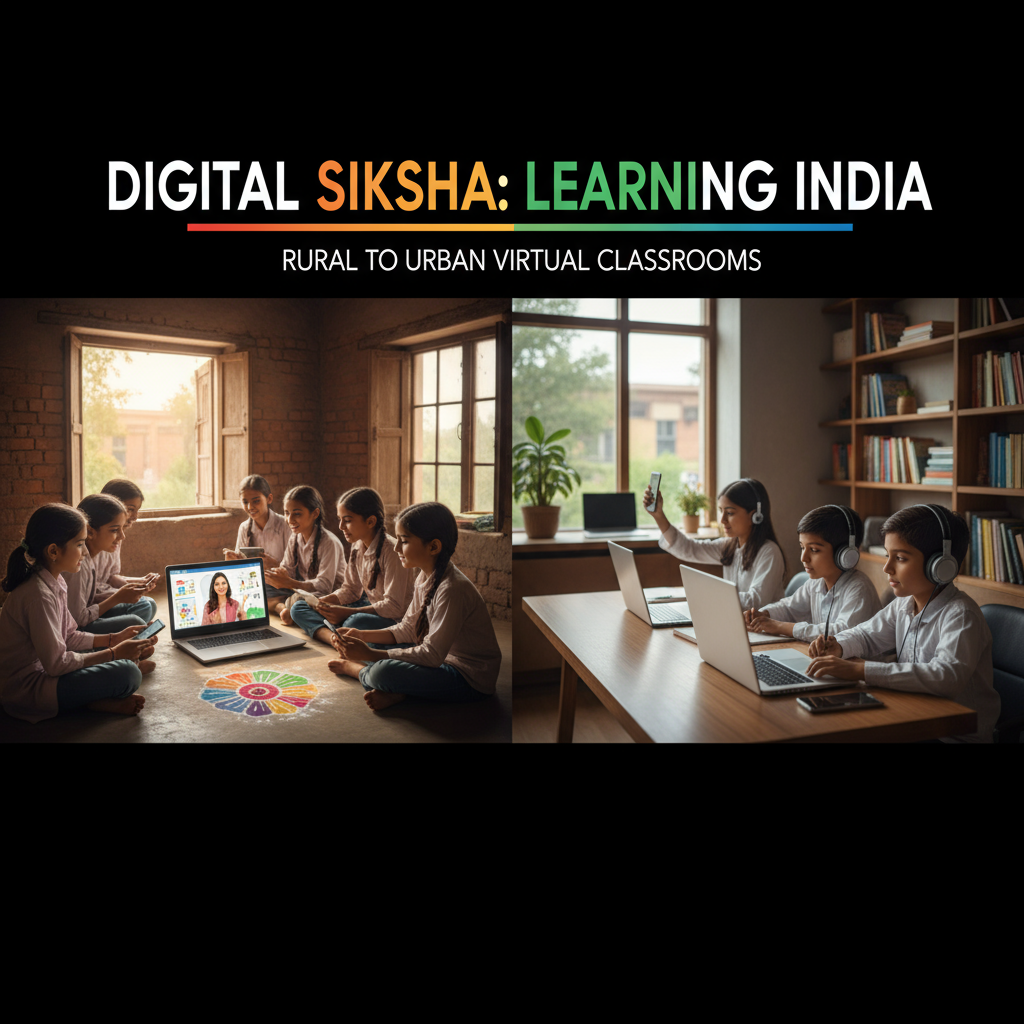

Educational and Age-Based Divides

COVID-19: The Great Revealer

The pandemic’s shift to online learning brutally exposed India’s digital fault lines:

Children with Disabilities:

- 56.5% of children with disabilities faced difficulties attending online classes

- 77% could fall behind due to inability to access distance learning

- 71% finding it difficult to cope with COVID-19 educational scenario

Socio-Economic Impact:

- 320 million learners transitioned to e-learning, but not all successfully

- 32 million children already out of school pre-pandemic, majority from disadvantaged classes

- Proportion unable to access online learning particularly high among low-income and low-caste families

Gender Dimension:

- Where multiple children share single device, male child given priority

- Girls in vulnerable households face increased domestic duties limiting online education access

Teacher Challenges:

- Teachers not trained enough; disabled students not their priority

- Teachers finding online learning ineffective, unable to maintain emotional connection or meaningfully assess learning

Linguistic Barrier

80% of internet content is in English, limiting non-English speakers:

- States with English competency (Kerala) digitally ahead vs. lagging (West Bengal)

- Vernacular content scarcity, especially for regional languages

Age Divide

Elderly populations struggle with digital interfaces, dependent on intermediaries:

- Rural older adults: 54% internet access vs. Urban: 66%, Suburban: 61%

- Older adults perceiving technology as “too complicated,” “too hard to learn”

- Rural youth (15-24 age): 43.6% can send emails, 31% can do online banking—still significant gaps

Skills Gap: The Second-Level Divide

Basic Digital Skills Deficiency

Having a device doesn’t mean knowing how to use it meaningfully:

Email Skills:

- Rural: Only 20% can send/receive emails

- Urban: 40% can send/receive emails

- Rural youth (15-24): 43.6%; 15-29: 43.4%

Online Banking:

The Usage Paradox:

- Over 55% Indians have broadband but only 20% can use internet meaningfully

- 94% rural households have mobile ownership but limited ability to leverage for education, health, financial services

- Account ownership high but usage low among vulnerable groups—the “banked but unbanked” phenomenon

Content Relevance

- Lack of localized vernacular content limiting meaningful engagement

- Service-oriented content in regional languages needed but scarce

- Digital literacy programs insufficient; functional skills remain elusive

Constitutional and Policy Framework

Right to Internet Access: Kerala HC Landmark Judgment

In a groundbreaking 2019 ruling, the Kerala High Court declared internet access as a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution:

Case: Faheema Shirin v. State of Kerala

Background: College student challenged restrictions on mobile phone usage (6 PM-10 PM) in girls’ hostel, arguing it hampered learning by depriving internet access.

Court’s Declaration:

- “Right to access Internet is part of right to privacy and right to education under Article 21”

- “When Human Rights Council of UN found right to internet access is fundamental freedom and tool to ensure right to education, any rule impairing said right cannot be permitted”

- Restrictions on internet access disproportionately affect fundamental rights, especially of students

Significance:

- Internet access crucial for participation in modern education and informed decision-making

- Digital resources essential for learning and communication

- Article 21 interpreted to include digital access alongside privacy, education, livelihood

Emerging Constitutional Discourse

Should internet access be a fundamental right?

- Only 65% Indian houses have internet; one-third population excluded from essential services

- Digital infrastructure as public good vs. private commodity debate

- Not just provisioning right but ensuring simple, affordable, safe accessibility

- Material, educational, legislative interventions making digital infrastructure meaningful, accessible, non-extractive

Socio-Economic Impacts: Who Wins, Who Loses?

Education

- Online learning inaccessible to digitally excluded during COVID-19

- Virtual education deepening inequality; rural students disadvantaged

- Gini index worsening as digital divide intersects educational inequality

Employment

- Recruitment processes shifting online; internet literacy determining job prospects

- Digital skill gap limiting youth employability

- Gender gap in employment widening without digital access

Financial Inclusion

- PM Kisan: Only 27% beneficiaries receive DBT digitally, highlighting gaps

- Digital-only government services excluding non-connected citizens

Healthcare

- Telemedicine inaccessible to rural, elderly, digitally illiterate

- COVID-19 medical care via video conferencing: Rural disadvantage

Opportunity Cost

E-governance, online education, tele-health, digital payments—all premised on access. Digital India’s promise unfulfilled for marginalized without bridge.

Policy Recommendations: Towards Inclusive Digital India

1. Strengthening Infrastructure

Last-Mile Connectivity:

- FTTH (Fiber to the Home), strong Wi-Fi networks reaching every home, school, clinic

- Not just village office but comprehensive household coverage

- BharatNet Phase III acceleration with accountability mechanisms

Technology Solutions:

- Leveraging satellite internet (Direct-to-Device) for remote areas

- 6G planning for bridging digital divide in rural areas

- Affordable broadband: Universal Service Obligation Fund (USOF) optimized

2. Bridging Skills Gap

Mass Digital Literacy:

- Comprehensive campaigns targeting 50 crore adults

- NGO-led initiatives integrating with national frameworks

- Mobile digital labs, women-led microenterprises replicating successful models

Targeted Interventions:

- Women-focused programs addressing functional literacy, cyber safety

- SC/ST-specific capacity building countering caste-based exclusion

- Elderly-friendly interfaces: voice-based, vernacular UX

Educational Integration:

- Digital and financial literacy in school curricula

- Vocational training opportunities for youth harnessing demographic dividend

3. Addressing Gender Gap

Access Enhancement:

- Subsidized smartphones for BPL women

- Household education on benefits of women’s digital access

- Wider connectivity, penetration in rural areas

Empowerment and Safety:

- Digital education enabling women to leapfrog traditional development divide

- Cyber safety awareness, reporting mechanisms for online harassment

- Challenging patriarchal norms restricting digital space access

4. Content and Usability

Vernacular Content:

- Regional language content creation incentivized

- Government services, educational materials in local languages

Universal Design:

- Accessible interfaces for persons with disabilities

- Low-bandwidth, simplified designs for low-literacy users

5. Governance and Coordination

Unified Framework:

- Single-window clearance, coordination among BBNL, BSNL, CSC-SPV, state governments

- Clear guidelines, fast-track approvals, performance-based incentives

Accountability Mechanisms:

- Streamlined grievance redressal, effective monitoring

- Public-private partnerships with defined responsibilities

6. Sustainable Models

Revenue Generation:

- Local entrepreneurs, small ISPs participating in ecosystem

- Community ownership models ensuring sustainability

Affordability:

- Zero-rating essential services (education, health, governance)

- Tiered pricing enabling basic connectivity for all

7. Research and Monitoring

Data-Driven Policymaking:

- Disaggregated data (gender, caste, age, geography, income) tracking exclusion

- Periodic assessments beyond CAMS; real-time indicators

Impact Evaluation:

Way Forward: From Access to Empowerment

Short-Term (1-2 years)

- Complete BharatNet last-mile connectivity to all 250,000 GPs

- Launch massive digital literacy campaign in 100,000 villages

- Pilot women-focused digital empowerment in 10,000 villages

- Expand vernacular content by 300%

Medium-Term (3-5 years)

- Achieve 95% rural broadband coverage with quality benchmarks

- 50% rural citizens proficient in basic digital skills (email, online banking)

- Eliminate gender gap in internet access and usage

- Fiber-optic reach 50% rural households

Long-Term (5-10 years)

- Universal digital inclusion: 100% households with affordable, quality broadband

- Digital literacy parity: Rural skills matching urban

- India as model for inclusive digital development globally

- Right to internet access constitutionally recognized, legislatively protected

Conclusion: Building Bridges, Not Just Highways

India’s digital revolution presents a profound paradox: 76.3% broadband penetration coexisting with stark inequalities that deny millions meaningful digital participation.

The CAMS 2022-23 revelation is unambiguous: Access is improving but skills are lagging—only 20% rural, 40% urban can email; only 37.8% can do online banking. This isn’t just a technical gap; it’s a social justice crisis.

The multi-dimensional nature of India’s digital divide demands urgent attention:

Geographic disparity: Delhi (>90%) vs. Arunachal Pradesh (60.2%) broadband; rural (83.3%) vs. urban (91.6%).

Caste-class nexus: General (84.1%) vs. ST (64.8%) access; poorest (71.6% lacking) vs. richest (1.9% lacking).

Gender gap: Women (33.3%) vs. men (57.1%) internet usage; women 40-56% less likely to use mobile internet.

BharatNet’s promise vs. reality: 2.14 lakh GPs connected but last-mile incomplete, coordination gaps, sustainability concerns.

The Kerala High Court’s landmark 2019 judgment declaring internet access as fundamental right under Article 21 provides constitutional foundation for digital inclusion. But rights on paper mean little without infrastructure, skills, and genuine opportunity.

This must be understood as a social justice issue transcending technology—encompassing equity, inclusion, and empowerment. As one MeitY official eloquently stated: “Real Digital India is when a woman in a far-flung village logs into a portal claiming her entitlements”.

The hard truth: India has built digital highways but too many don’t know how to drive. Investment in users is as critical as infrastructure.

Constitutional question looms: Should internet access be recognized as fundamental right ensuring simple, affordable, safe accessibility?

Gender digital divide can accelerate India’s digital revolution once three barriers addressed: Access, digital literacy, cyber safety.

NGO innovations—mobile labs, women-led microenterprises, community ownership—offer sustainable pathways.

True digital inclusion moves beyond connectivity to meaningful participation, tangible outcomes, empowerment.

Digital divide represents the digital frontier of inequality requiring urgent, comprehensive, sustained action.

Vision: India where every citizen—regardless of geography, gender, caste, class, age—participates fully in digital economy, reaping benefits of technology revolution.

Bridging India’s digital divide is not merely an infrastructure challenge but a transformative social project ensuring “no one left offline” in the nation’s digital future.

+ There are no comments

Add yours