Key Highlights

- Investment Breakthrough: PLI scheme attracted ₹1.76 lakh crore committed investments across 806 approved applications in 14 strategic sectors by March 2025, exceeding initial targets

- Production Surge: Total sales by PLI participants crossed ₹16.5 lakh crore with electronics production rising 146% from ₹2.13 lakh crore (FY21) to ₹5.25 lakh crore (FY25)

- Employment Engine: Over 12 lakh direct and indirect jobs created since PLI launch, with quality formal manufacturing employment across tier-2 and tier-3 cities

- Export Transformation: Mobile phone exports surged 95% YoY to $1.8 billion in September 2025, with cumulative pharmaceutical exports worth ₹1.70 lakh crore in three years

- Import Substitution: India transitioned from net importer (₹1,930 crore deficit in FY22) to net exporter of bulk drugs (₹2,280 crore surplus in FY25)

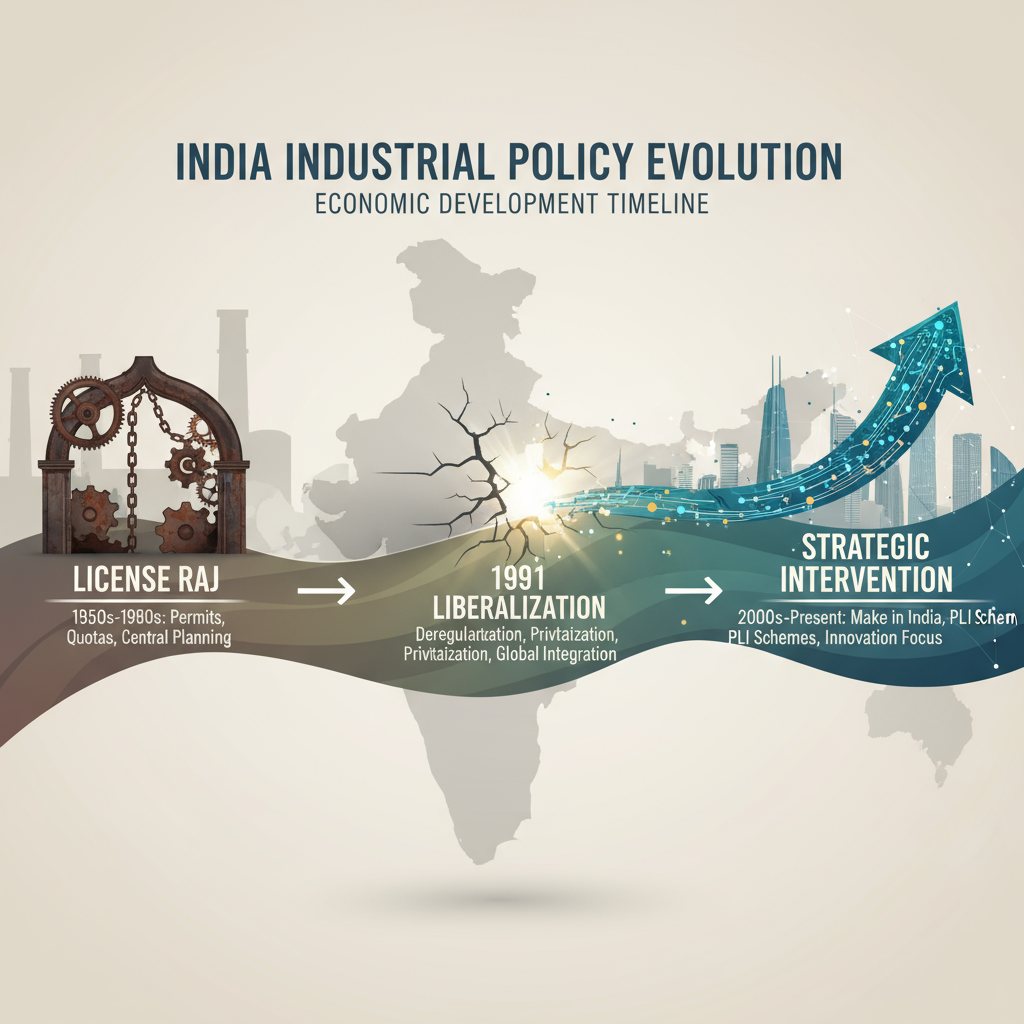

The Journey from License Raj to Strategic Clarity

India’s industrial policy has undergone a remarkable transformation over seven decades, evolving from heavy-handed state control to strategic market-friendly interventions that demonstrate true policy maturity.

Post-Independence Era: The License Raj Legacy (1947-1991)

The early decades of independent India were defined by extensive state control over industrial production. The Industrial Policy Resolution of 1956 reserved “commanding heights” of the economy for the public sector, while private industry operated under restrictive licensing systems that determined who could produce what, where, and how much.

This import substitution industrialization strategy aimed to build self-sufficiency but ultimately limited competitiveness by insulating domestic producers from global competition. The License Raj created inefficiencies, corruption, and the infamous “Hindu rate of growth” that kept India’s economy underperforming for decades.

Liberalization Phase: Markets Without Strategy (1991-2015)

The 1991 economic reforms dismantled industrial licensing and opened sectors to private investment, marking a watershed moment in India’s economic history. Trade liberalization and permissive industrial policies replaced the restrictive framework, unleashing entrepreneurial energy that had been constrained for decades.

However, a critical challenge remained: Manufacturing growth acceleration and employment generation proved elusive despite reforms. While services sectors like IT flourished, manufacturing’s share of GDP stagnated around 15-17%, far below the levels achieved by other Asian tigers during their industrialization phases.

Strategic Re-engagement: Make in India Era (2015-2020)

The 2014 launch of Make in India signaled renewed governmental focus on manufacturing, recognizing that markets alone were insufficient to build competitive industrial capabilities. This period saw policy experimentation across sectors as policymakers grappled with how to strategically intervene without reverting to License Raj-style controls.

The Make in India initiative aimed to raise manufacturing’s share of GDP to 25% while creating millions of jobs for India’s young population. It represented a philosophical shift: acknowledging that strategic state intervention could catalyze industrial development without stifling private enterprise.

Atmanirbhar Bharat: Self-Reliance 2.0 (2020-Present)

COVID-19 exposed critical supply chain vulnerabilities that crystallized thinking around strategic self-reliance. In May 2020, Prime Minister Modi launched the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan with a ₹20 lakh crore economic package aimed at making India self-reliant across strategic sectors.

This isn’t the protectionism of the past but strategic capability building. The mission focuses on integrating India into global value chains from a position of strength rather than retreating into import substitution. It encompasses five strategic pillars: Economy, Infrastructure, Systems, Democracy, and Demand – with four key enabling factors: Land, Labour, Liquidity, and Laws.

PLI Scheme: The Centerpiece of Modern Industrial Strategy

The Production Linked Incentive scheme represents the most significant expression of India’s industrial policy maturity, demonstrating sophisticated understanding of how to strategically deploy state resources for industrial development.

Design Architecture: Why PLI Is Different

Launch and Expansion: Initially targeting just 3 sectors in March 2020 (mobile phones, electrical components, medical devices), PLI rapidly expanded to 14 strategic sectors by 2021. This phased approach allowed for learning and refinement before scaling. pib.gov

The 14 covered sectors include: Electronics (mobile phones, electronic products, telecom & networking); Clean energy (solar PV modules, Advanced Chemistry Cell batteries); Auto sector (automobiles and auto components); Pharma (pharmaceuticals and medical devices); plus specialty steel, white goods, textiles, food processing, and drones. PLIscheme

Financial Commitment: Total incentive outlay reached ₹1.97 lakh crore, with committed investments hitting ₹1.76 lakh crore by March 2025 across 806 approved applications. This represents one of the world’s largest manufacturing incentive programs by any single nation.

Key Features Demonstrating Maturity

Outcome-Based Approach: Unlike traditional subsidies, PLI incentives are disbursed only after production occurs, based on incremental sales rather than merely capacity creation. This rewards performance over promises, ensuring taxpayer money flows only to successful ventures.

Strategic Sectoral Selection: Target sectors were chosen based on high import dependence, employment generation potential, export competitiveness opportunities, and dual-use technology applications. This strategic targeting contrasts sharply with the indiscriminate industrial licensing of the past.

Technology and Scale Requirements: Minimum investment thresholds ensure serious players while technology transfer and local value addition mandates encourage both domestic capability building and foreign investment. This balances the need for foreign capital with indigenous capability development.

Quantifiable Achievements: Evidence of Policy Success

Electronics: From Importer to Global Hub

India’s electronics manufacturing sector has witnessed a sixfold production increase – from ₹1.9 lakh crore in 2014-15 to ₹11.3 lakh crore in 2024-25. This transformation positions India as the world’s second-largest mobile manufacturer, a remarkable achievement for a country that was 75% import-dependent just a decade ago. pib.gov

Mobile manufacturing tells an even more dramatic story:

Production Units: From just 2 manufacturing units in 2014-15 to around 300 units today – a 150-fold expansion.

Production Value: Mobile phone production surged from ₹18,000 crore to ₹5.45 lakh crore – a 28-fold increase.

Export Explosion: Mobile phone exports grew from ₹1,500 crore to nearly ₹2 lakh crore – a 127-fold increase. September 2025 alone saw $1.8 billion in mobile exports, up 95% year-on-year. pib.gov

Import Substitution: Mobile phone imports plummeted from 75% of domestic demand to just 0.02% – virtual elimination of import dependency.

Value Addition: Electronics value addition jumped from 30% to 70%, with targets to reach 90% by FY27. This demonstrates genuine manufacturing depth rather than mere assembly operations.

Pharmaceuticals: Building Drug Security

India’s pharmaceutical industry, ranking 3rd globally by volume, has been strengthened through PLI support. The sector transitioned from being a net importer of bulk drugs (₹1,930 crore deficit in FY 2021-22) to a net exporter (₹2,280 crore surplus in FY 2024-25). pib

In the first three years of PLI implementation, pharma sales crossed ₹2.66 lakh crore, including exports worth ₹1.70 lakh crore. Domestic value addition in the sector reached 83.70% by March 2025, indicating genuine manufacturing capability rather than dependence on imported active pharmaceutical ingredients.

The industry supplies over 50% of global vaccine demand and nearly 40% of generic drugs to the United States, with projections to grow from current levels to $130 billion by 2030 and $450 billion by 2047.

Automotive Sector: Driving Electric Mobility

Under PLI, the automotive sector attracted committed investments worth ₹67,690 crore, with ₹14,043 crore invested by March 2024, generating over 28,884 jobs. The scheme supports 19 categories of Advanced Automotive Technology vehicles and 103 categories of AAT components.

The automotive industry contributes 7.1% to India’s GDP and 49% to manufacturing GDP, producing over 3.10 crore vehicles in FY25, making India the fourth-largest automobile producer globally. PLI aims to make India a global electric vehicle and clean-tech hub, aligned with the FAME initiative.

Food Processing: Value Addition in Agriculture

With 171 approved applications by October 2024, the food processing sector has seen investments exceeding ₹8,910 crore, with ₹1,084 crore disbursed in incentives. The scheme complements initiatives like PM-FME and PMKSY, aiming to modernize processing units, enhance branding of Indian food products, and boost value-added exports.

Employment Impact: Quality Job Creation

Over 12 lakh direct and indirect jobs have been generated since PLI launch, with significant employment creation in tier-2 and tier-3 cities, spreading industrial development beyond traditional manufacturing hubs. This represents quality formal sector employment with higher wages and better working conditions than informal sector alternatives.

The scheme has also catalyzed MSME ecosystem development, with 176 MSMEs among PLI beneficiaries in sectors including bulk drugs, medical devices, pharma, telecom, white goods, food processing, textiles, and drones.

Atmanirbhar Bharat: Strategic Framework for Self-Reliance

The Atmanirbhar Bharat mission provides the overarching strategic framework within which PLI and other industrial policies operate.

Conceptual Clarity: Not Protectionism

Atmanirbhar Bharat explicitly rejects inward-looking protectionism in favor of strategic capability building. The goal is integration with global value chains from a position of strength – achieving self-sufficiency in critical sectors while maintaining competitive participation in others.

The mission emphasizes “local for global,” “made for world,” and “vocal for local” themes that balance domestic capability building with global competitiveness.

The Five Strategic Pillars

Economy: Quantum leap converting adversity into opportunity through expanded domestic production.

Infrastructure: Modern infrastructure as foundation for New India, enhancing connectivity, logistics, and industrial efficiency through initiatives like PM Gati Shakti.

Systems: 21st-century technology and innovative governance replacing outdated processes through digital transformation.

Democracy: Robust democratic framework providing institutional mechanisms for self-reliance through stakeholder participation and transparency.

Demand: Leveraging domestic demand intelligently to ensure full capacity utilization while stimulating consumption.

Four Key Enabling Factors

Land: Reforms enabling easier land acquisition and development of industrial corridors.

Labour: Skill development programs and labor law reforms balancing flexibility with worker protection.

Liquidity: Enhanced credit access, MSME support schemes, and efficient debt resolution mechanisms.

Laws: Regulatory simplification, GST rationalization, and compliance burden reduction.

Tangible Achievements

Import Substitution Progress: A 2020 Acuite Ratings report identified 40 sub-sectors accounting for ~$33.6 billion imports from China that India could replace through domestic manufacturing. This represents potential savings of ~0.3% of GDP in trade deficit reduction. ibef

Indigenous Production: Electronics Component Manufacturing Scheme approved with ₹22,919 crore outlay aims to attract investments worth ₹59,350 crore and generate over 91,000 direct jobs.

Defense Indigenization: 72 items previously imported are now manufactured exclusively in India by DPSUs.

PPE Self-Sufficiency: Within 60 days of Atmanirbhar Bharat launch, India generated indigenous PPE kit supply chains, demonstrating rapid response capability.

Vaccine Success: India launched the world’s largest vaccination drive with two “Made in India” vaccines – Covaxin and Covishield.

Signs of Industrial Policy Maturity: Critical Analysis

Evidence-Based Policymaking

The establishment of monitoring systems like the New Industrial Policy Observatory (NIPO) enables systematic analysis of policy evolution and effects. Course corrections based on implementation feedback demonstrate learning capacity – a hallmark of mature policy systems.

PLI scheme design incorporated lessons from earlier initiatives, with sectoral variations reflecting understanding that one-size-fits-all approaches don’t work for diverse industrial contexts.

Whole-of-Government Coordination

Despite involving multiple ministries, PLI shows implementation coherence rare in Indian governance. Integration with Make in India, Digital India, and Skill India missions demonstrates capability for coordinated action across traditional bureaucratic silos.

Accelerated Policy-Driven Transitions

The Bharat Stage leapfrog (BS4 to BS6) demonstrated state capacity for accelerating transitions faster than market mechanisms alone would achieve. This required coordination between policymakers, automobile manufacturers, oil companies, and infrastructure providers.

Balancing Domestic and Global Objectives

PLI simultaneously reduces import dependence while enhancing export competitiveness – a sophisticated balancing act. Attracting FDI while building indigenous capabilities requires nuanced policy design that PLI largely achieves.

Sectoral Differentiation

Capital-intensive sectors (steel, ACC battery) receive different treatment than labor-intensive sectors (textiles, food processing). Technology transfer requirements vary by sector maturity, demonstrating understanding of sectoral differences.

Phased Implementation and Learning

The initial 3-sector pilot expanding to 14 sectors exemplifies cautious scaling. Learning from early sectors informed later designs, with continuous monitoring enabling mid-course corrections.

Persistent Challenges: Areas Requiring Further Maturation

Assembly vs. Value Addition

PLI critics note that the scheme doesn’t sufficiently differentiate between value-added manufacturing and import-assembly operations. Some beneficiaries engage primarily in assembling imported components rather than developing deep local supply chains.

This risks creating shallow industrialization with limited innovation, technology absorption, or sustainable competitiveness. Deeper local sourcing mandates and technology development incentives may be necessary.

Moving Up the Value Chain

Production remains concentrated in low-value goods more than high-value products. The US and EU primarily trade high-value goods, presenting a competitiveness challenge for India as it seeks to capture premium market segments.

R&D Insufficiency

Inadequate attention to Research and Development in export-oriented policies limits innovation capability. Manufacturing competitiveness increasingly requires innovation capacity, not just production efficiency. Stronger linkages between industry and research institutions are essential.

Implementation Coordination Challenges

Multiple ministries implementing PLI create potential for confusion and inconsistency. State-level coordination challenges compound these difficulties. Single-window clearances and dedicated project management units could address these issues.

Labor-Intensive Sector Coverage

Parliamentary Standing Committee recommendations to expand PLI to labor-intensive sectors like footwear, leather, toys, and furniture reflect current scheme’s relatively capital-intensive focus. Broader sectoral coverage would maximize employment generation potential.

Workforce Development: Critical Enabler

India’s industrial transformation depends critically on aligning workforce capabilities with evolving industrial landscape requirements.

Reskilling and Upskilling Imperatives

The Indian industrial sector requires massive workforce transformation to support advanced manufacturing. Current skill levels lag requirements in areas like electronics, pharmaceuticals, and automotive components.

Gender disparities in skill development need particular attention, as women remain underrepresented in manufacturing employment despite comprising half the potential workforce.

Online Learning and Career Advancement

Digital skill enhancement platforms play significant roles in democratizing access to industrial training. Integration with formal education and on-the-job training creates comprehensive development pathways.

Research shows reskilling correlates with better career progression, improving both retention and productivity. This creates virtuous cycles where investment in human capital generates returns for both workers and employers.

Comparative Perspective: India in Global Context

Return of Industrial Policy Globally

India’s strategic industrial policy isn’t isolated but part of a global trend. Post-pandemic supply chain security concerns and US-China geopolitical competition are driving industrial strategy worldwide. The US CHIPS Act, European Green Deal Industrial Plan, and similar initiatives demonstrate that active industrial policy has returned to mainstream economic thinking.

India’s Unique Positioning

Late mover advantages allow India to learn from others’ mistakes while avoiding pitfalls. Democratic constraints requiring broader stakeholder buy-in ensure more sustainable policies than authoritarian alternatives. Scale advantages from a large domestic market de-risk investments, making India attractive despite challenges.

Policy Recommendations: Next Phase of Maturity

Deepening Value Addition

Moving from assembly to component manufacturing requires technology licensing support, backward integration incentives, and R&D infrastructure development. Current incentives should be weighted toward domestic value addition percentages.

Innovation Ecosystem Building

R&D tax incentives, research grants, industry-research institution partnerships, and intellectual property protection and commercialization support would strengthen innovation capabilities essential for long-term competitiveness.

MSME Integration

Ensuring PLI benefits cascade to MSME suppliers through vendor development programs and cluster development for ancillary industries would broaden the impact while building resilient supply chains.

Sustainability Integration

Green manufacturing incentives, circular economy principles, and carbon border adjustment mechanism preparedness should be integrated into industrial policy to ensure long-term viability in an environmentally conscious global economy.

State-Level Differentiation

Enabling states to design complementary schemes, developing regional industrial clusters based on comparative advantage, and fostering competitive federalism in attracting investments would leverage India’s federal structure as a strength.

Measuring Success: Comprehensive Metrics

Quantitative Indicators

Manufacturing share in GDP (current ~17%, target 25%), FDI inflows in manufacturing, export growth and diversification, employment generation in formal sector, patent filings, and R&D expenditure provide objective measures of progress.

Qualitative Indicators

Moving up global value chains, technology absorption and adaptation, brand recognition of Indian manufactured goods globally, and reduction in import dependence for critical items indicate deeper transformation beyond mere quantitative growth.

Institutional Indicators

Policy stability and predictability, implementation capacity at central and state levels, coordination across ministries and agencies, and responsiveness to feedback measure the maturity of institutional frameworks supporting industrial development.

Conclusion: The Maturity Moment

India’s industrial policy has demonstrably matured, evolving from License Raj inertia through liberalization ambivalence to current strategic clarity. The PLI scheme represents a watershed moment – an outcome-based, sectoral-focused, evidence-informed approach that balances state intervention with market mechanisms.

Tangible results validate the approach: ₹1.76 lakh crore investments, ₹16.5 lakh crore in sales, 12 lakh jobs created, and dramatic transformations in electronics, pharmaceuticals, and automotive sectors demonstrate that strategic industrial policy works when properly designed and implemented.

Challenges certainly persist: Value addition depth, R&D intensity, labor-intensive sector coverage, and implementation coordination require continued attention. The next phase of maturity demands deeper integration with skill development, sustainability principles, MSME ecosystems, and state-level innovation.

Industrial policy isn’t an ideological choice between state and market but a pragmatic tool for strategic capability building. The global context showing the return of industrial policy worldwide validates India’s approach while providing opportunities to benchmark against international best practices.

The ultimate test lies ahead: Whether India can translate manufacturing growth into quality employment, technological leadership, and export competitiveness that sustains the journey toward a $5 trillion economy and beyond. Maturity is reflected not just in policy design but in sustained implementation, continuous learning, and institutional coordination over the coming decade.

+ There are no comments

Add yours