Key Highlights

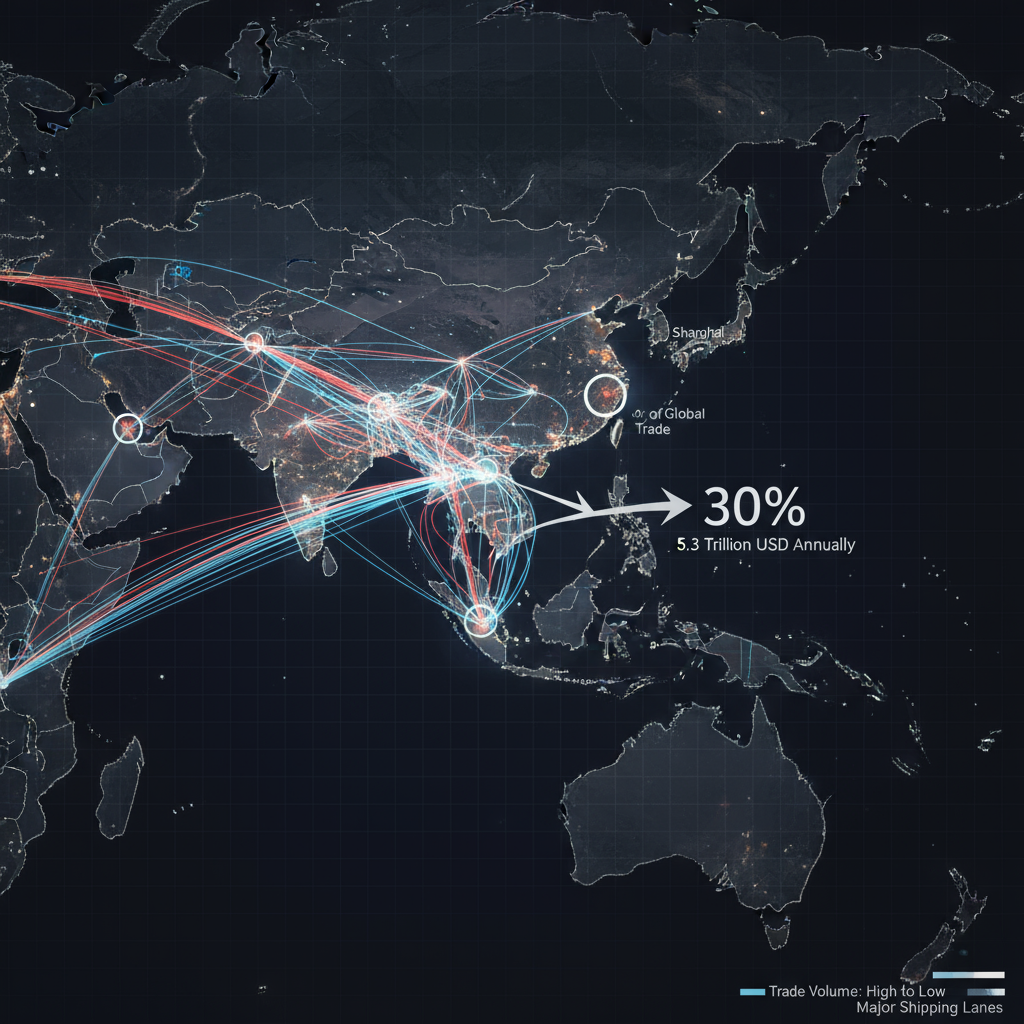

- $5.3 trillion in global trade transits South China Sea annually (21% of world trade), with one-third of global shipping passing through these contested waters

- China’s nine-dash line claims 90% of South China Sea, violating UNCLOS provisions on territorial seas, EEZs, and continental shelves of neighboring countries

- Seven artificial islands militarized by China since 2013, creating 2,470 acres of new land with airstrips, missile systems, and naval facilities

- 2016 UNCLOS tribunal ruling rejected China’s historic claims as having “no legal basis,” but Beijing continues assertive actions while rejecting international arbitration

- Critical energy chokepoint with 40% of global petroleum products and 80% of China’s oil imports passing through Strait of Malacca and SCS waters

The World’s Most Contested Waters

The South China Sea stands as the epicenter of one of the most significant maritime disputes of the 21st century, where territorial sovereignty, international law, and global economic security converge in a volatile mixture of competing claims and strategic interests. Spanning approximately 3.5 million square kilometers, this vital waterway connects the Indian and Pacific Oceans while serving as the primary trade route for the world’s largest economies.

At the heart of this dispute lies China’s controversial nine-dash line—a U-shaped boundary that encompasses nearly 90% of the South China Sea and directly challenges the maritime rights of Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan under established international law. This expansive claim has transformed what should be shared international waters into a potential flashpoint for global conflict, with implications extending far beyond regional politics to threaten the $5.3 trillion in annual trade that depends on these sea lanes.

The escalating tensions have already begun impacting global commerce, with freight rates on key Asian routes more than doubling in recent periods, demonstrating how quickly regional disputes can translate into worldwide economic consequences. As China continues building artificial islands and militarizing disputed features, while the international community responds with Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs), the South China Sea has become a critical test of whether international law or unilateral power will govern the oceans of the future.

Strategic Significance: The Lifeline of Global Commerce

Maritime Trade Hub of Unprecedented Scale

The South China Sea’s role as a global trade artery cannot be overstated in its economic significance. UNCTAD estimates that approximately 80% of global trade by volume and 70% by value is transported by sea, with the South China Sea handling one-third of all global shipping. This concentration makes it the world’s most valuable shipping corridor, surpassing even the Suez Canal in economic importance. chinapowercsis

Trade Volume Breakdown by Major Economies:

- China: 64% of maritime trade (approximately $1.47 trillion)

- Japan: 42% of maritime trade ($240 billion)

- India: 30.6% of all trade in goods ($189 billion)

- United States: 14% of maritime trade ($208 billion)

- Germany: 9% of trade flows ($215 billion)

The strategic vulnerability becomes evident when considering that alternative routes around the South China Sea could add $1 million per voyage in additional costs, with delays of 2-6 weeks for major shipping routes. Such disruptions would create cascading effects throughout global supply chains, potentially contributing 0.7% to global core goods inflation based on recent disruption models.

Energy Security and Resource Dependencies

The South China Sea’s importance extends beyond general cargo to critical energy flows that power the world’s largest economies. 40% of global petroleum products transit through these waters annually, making any disruption potentially catastrophic for global energy security. atlasinstitute

Critical Energy Flows:

- 80% of China’s oil imports pass through the Strait of Malacca

- 45% of global crude oil shipments transit the region

- 42% of global propane movements

- Estimated 11 billion barrels of oil reserves beneath the seabed

- 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in proven and potential reserves

The Strait of Malacca, connecting the South China Sea with the Indian Ocean, represents a particularly critical chokepoint where 25% of all traded goods pass through a narrow 1.7-mile-wide channel at its narrowest point. This geographic vulnerability has historically been termed the “Malacca Dilemma” by Chinese strategic planners, driving Beijing’s efforts to secure alternative routes and assert control over South China Sea shipping lanes.

Fisheries and Food Security

Beyond trade and energy, the South China Sea supports rich fisheries that provide protein security for over 3 million people across the region. These waters account for 12% of global fish catch, making fishing rights disputes particularly contentious for coastal communities dependent on maritime resources. The overlapping claims have led to numerous incidents involving fishing vessels, coast guard patrols, and competing enforcement actions that escalate diplomatic tensions.

China’s Expansive Claims: The Nine-Dash Line Controversy

Historical Claims and Legal Foundations

China bases its South China Sea claims on what it terms “historic rights” dating back centuries, formalized through the controversial nine-dash line first published by the Republic of China government in 1947. Originally an eleven-dash line, it was reduced to nine dashes in 1952 when Mao Zedong removed two dashes in the Gulf of Tonkin during warming relations with North Vietnam.

China’s Four Pillars of Claims:

- Sovereignty over all islands in the South China Sea

- Internal waters, territorial seas, and contiguous zones around claimed islands

- Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) and continental shelves of these islands

- Historic rights to resources within traditional fishing grounds

However, UNCLOS Article 3 clearly states that “every State has the right to establish territorial sea breadth up to 12 nautical miles” from established baselines, while Article 57 limits EEZs to 200 nautical miles from coastal baselines. China’s nine-dash line grossly exceeds these internationally recognized limits, overlapping with legitimate EEZs of Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Brunei.

Artificial Islands and Militarization Strategy

China’s most assertive action has been the construction of artificial islands on disputed reefs and shoals, fundamentally altering the region’s geographic and strategic landscape. Between 2013 and 2015, China created approximately 5 square miles (2,470 acres) of artificial land across seven disputed sites in the Spratly Islands chain.

Major Artificial Island Installations:

- Mischief Reef: 5.52 square kilometers with 3,125-meter airstrip

- Fiery Cross Reef: 2.74 square kilometers with military facilities

- Subi Reef: 3.95 square kilometers forming triangular defense position

- Military capabilities: Radar systems, anti-ship missiles, surface-to-air missiles, fighter jets, naval berths

These installations serve dual purposes: establishing physical control over disputed areas while creating military bases that project Chinese power throughout the South China Sea. The $50 billion investment in artificial island construction demonstrates China’s commitment to irreversible facts on the ground regardless of international legal opinions.

Legal Stance and UNCLOS Rejection

Despite ratifying UNCLOS in 1996, China has selectively rejected the convention’s jurisdiction when rulings contradict Chinese interests. The 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling in favor of the Philippines found that China’s nine-dash line claims had “no legal basis” and violated UNCLOS provisions on territorial seas and EEZs.

Key 2016 Tribunal Findings:

- China had not exercised exclusive control historically over nine-dash line waters

- No legal basis exists for China’s historic rights claims

- Several Chinese-controlled features do not qualify as islands under UNCLOS

- China’s activities violated Philippines’ sovereign rights in its EEZ

China’s categorical rejection of this ruling, with President Xi Jinping declaring that China’s “territorial sovereignty and marine rights will not be affected by the so-called ruling in any way,” demonstrates Beijing’s willingness to defy international arbitration when it conflicts with core national interests.

Regional and International Responses: Pushback and Accommodation

ASEAN’s Divided Response

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has struggled to present a unified response to China’s assertive actions, reflecting the organization’s consensus-based decision-making and varying levels of economic dependence on China. While Philippines and Vietnam have been most vocal in challenging Chinese claims, other members have remained silent or conciliatory due to economic dependencies and bilateral relationships.

Varied ASEAN Positions:

- Philippines: Direct legal challenge through international arbitration

- Vietnam: Diplomatic protests and competing island construction

- Malaysia: Quiet diplomacy while maintaining sovereign claims

- Indonesia: Neutral stance while defending Natuna Islands EEZ

- Thailand/Cambodia: Economic partnership prioritization

The prolonged negotiations for a Code of Conduct since 2002 demonstrate China’s success in buying time through diplomatic processes while strengthening physical positions through island construction and militarization.

US Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs)

The United States has responded to Chinese assertiveness through regular Freedom of Navigation Operations, challenging what Washington views as excessive maritime claims that restrict international navigation rights. Since 2015, the US Navy has conducted dozens of FONOPs within 12 nautical miles of Chinese-controlled features to demonstrate that artificial islands cannot generate territorial claims.

FONOP Evolution and Intensity:

- 2015: First direct challenge with USS Lassen near Subi Reef

- 2020-2023: Increased frequency and scope of operations

- Multi-domain operations: Naval vessels, aircraft, and strategic bombers

- Allied participation: UK, France, Australia, Canada joining operations

However, expert analysis suggests that FONOPs have had limited effectiveness in countering China’s “salami-slicing” tactics and may actually fuel tensions while providing Chinese leaders with nationalist rallying points. The militarization of responses risks escalating from legal disputes to security competition.

China’s Strategic Responses and Escalation

China has responded to international pressure through multiple channels: diplomatic protests, military counter-maneuvers, and accelerated island construction. Chinese officials consistently frame FONOPs as violations of Chinese sovereignty while asserting navigation freedom for commercial vessels under Chinese protection.

Chinese Counter-Strategies:

- Maritime militia deployment for persistent presence around disputed features

- Coast Guard patrols asserting law enforcement jurisdiction

- Military exercises demonstrating defensive capabilities

- Economic incentives for regional countries to avoid confrontation

Implications for India and Global Governance

India’s Strategic Interests

India’s growing economic and strategic interests in the South China Sea make the dispute’s resolution critical for New Delhi’s Act East Policy and maritime security strategy. Approximately 55% of India’s trade passes through South China Sea waters, making any disruption directly impactful on Indian economic growth.

Indian Concerns and Interests:

- Energy security: Critical sea lanes for oil and LNG imports

- Trade routes: Alternative to land-based connectivity with East Asia

- Strategic balance: Preventing Chinese hegemony in Indo-Pacific

- Legal precedent: Upholding international law for global maritime governance

India has responded through enhanced naval cooperation with regional partners, participation in multilateral exercises, and diplomatic support for international arbitration while avoiding direct confrontation with China.

Precedent for Global Maritime Governance

The South China Sea dispute’s resolution will establish critical precedents for how international law, unilateral claims, and physical control interact in determining maritime boundaries. The failure to enforce international arbitration decisions could encourage similar challenges to established maritime boundaries in other disputed regions including the East China Sea, Arctic waters, and various island chains worldwide.

Global Implications:

- Erosion of UNCLOS authority if major powers ignore arbitration

- Incentivizing unilateral action over diplomatic resolution

- Weakening rules-based order in favor of might-makes-right approaches

- Encouraging regional arms races and militarization of maritime disputes

Policy Recommendations and Strategic Responses

Strengthening International Law Enforcement

Upholding UNCLOS requires collective international action beyond individual country responses:

Legal Framework Strengthening:

- Multilateral support for arbitration decisions

- Economic consequences for non-compliance with international rulings

- Enhanced maritime domain awareness through information sharing

- Capacity building for smaller coastal states to assert legitimate rights

Diplomatic Engagement and Confidence Building

Sustained diplomatic efforts remain essential despite current tensions:

Diplomatic Priorities:

- Track II diplomacy through academic and business channels

- Functional cooperation on fisheries management and environmental protection

- Incident prevention mechanisms reducing risk of escalation

- Multilateral forums providing alternative platforms for dialogue

Regional Security Architecture Enhancement

Building robust partnerships among like-minded nations:

Security Cooperation:

- QUAD enhancement with operational maritime cooperation

- ASEAN centrality in regional security discussions

- Minilateral partnerships for specific operational cooperation

- Information sharing on maritime domain awareness

Conclusion: Navigating Toward Stability

The South China Sea dispute represents one of the most complex challenges facing international governance in the 21st century, where economic interdependence, territorial sovereignty, and strategic competition create unprecedented tensions. With $5.3 trillion in annual trade at stake and multiple nuclear powers involved, the dispute’s peaceful resolution has become essential for global stability and prosperity.

China’s assertive approach through the nine-dash line claims, artificial island construction, and rejection of international arbitration has fundamentally challenged the post-World War II maritime order established through UNCLOS. The 2016 arbitration ruling’s rejection demonstrates how major powers can undermine international law when it conflicts with perceived national interests, creating dangerous precedents for global governance.

The international community’s response through FONOPs, diplomatic pressure, and multilateral cooperation has had mixed results in constraining Chinese actions while avoiding escalation to armed conflict. The divided ASEAN response reflects the challenge of balancing economic interests with security concerns in an era of great power competition.

For emerging powers like India, the South China Sea dispute presents both strategic challenges and opportunities. The need to uphold international law while managing economic relationships requires sophisticated diplomatic strategies that support rules-based order without triggering unnecessary confrontation.

+ There are no comments

Add yours