The Economic Crossroads: A Paradigm Shift in Policy Thinking

India stands at a critical juncture where two competing economic philosophies are vying for supremacy. The traditional Make in India approach, emphasizing manufacturing-led growth and job creation, faces a formidable challenge from proponents of an Innovate in India strategy centered on services and innovation.

This debate advocated for a fundamental shift from manufacturing to innovation-driven growth. Their arguments represent more than academic discourse—they constitute a blueprint for India’s economic future in an increasingly automated world.

Key Highlights:

- Manufacturing created only 4.5 million jobs vs 13+ million in services during FY25

- PLI scheme achieved just 36% of targeted job creation despite Rs 1.97 lakh crore outlay

- Automation threatens to displace up to 60 million manufacturing workers by 2030

- India commands 4.5% of global services exports, indicating competitive strength

- Services sector employs 182 million workers (30% of workforce) as of 2023-24

The Manufacturing Dream vs Reality

India’s Make in India initiative, launched with great fanfare, promised to transform the country into a global manufacturing hub. The Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, with its massive Rs 1.97 lakh crore outlay, was designed to catalyze domestic manufacturing across 14 sectors. pib.gov

However, the results tell a sobering story. By June 2024, the PLI scheme had created 5.84 lakh direct jobs—merely 36% of its 16.2 lakh target. Even in successful sectors like mobile manufacturing, the cost per job creation reached Rs 2.15 lakh per direct position, raising questions about efficiency and sustainability.

The traditional belief that small and medium-scale manufacturing would serve as the backbone of job creation appears increasingly outdated in the face of technological disruption. Despite decades of policy focus on manufacturing, India’s manufacturing share in GDP has remained stagnant below 20%.

The Automation Revolution: Why Manufacturing Jobs Are Disappearing

The most compelling argument for the innovation-first approach lies in the automation revolution sweeping global manufacturing. As Prasanna Tantri eloquently argued, “When the rest of the world is manufacturing with robots, if you manufacture manually, your product will not be competitive”.

McKinsey Global Institute estimates that automation could displace up to 60 million workers in India’s manufacturing sector by 2030. This technological disruption is not a distant threat—it’s happening now. India’s industrial robotics market is projected to reach $264.10 million by 2028, growing at 2.92% CAGR. investindia

The vulnerability is particularly acute for India’s 90% informal workforce, which lacks access to retraining programs and social security nets. Traditional manufacturing jobs in textiles, electronics, and assembly lines face the highest risk of automation, making the sector an unreliable foundation for long-term employment strategy.

The Services Advantage: Where Real Job Growth Happens

The data overwhelmingly supports the services-first argument. In FY25, for every manufacturing job created, services generated nearly three. Services sector employment reached 182 million workers in 2023-24, representing 30% of India’s workforce and adding 40 million workers over six years. niti.gov

Non-tradable services—including healthcare, education, retail, and personal services—offer particular promise. As Tantri noted, “The good thing about non-tradable jobs is that technology doesn’t change as much. You think about the barber 20-30 years ago versus now. It’s the same thing”.

The employment statistics are revealing:

- Healthcare: Added 830,000+ jobs in FY25

- Information Technology: Created 700,000+ positions

- Trade and Retail: Generated 1.9 million new jobs

- Personal Services: Added 4.6 million positions

The China Model: Why It Won’t Work for India

A critical aspect of the innovation argument concerns India’s ability—or inability—to replicate China’s manufacturing success. The historical context has fundamentally changed.

China achieved manufacturing dominance during an era of high globalization and unprecedented global trade expansion. China’s savings rate of 50% enabled massive investments, while India’s declining savings rate of 30% limits similar capital deployment.

More importantly, China leveraged an era when manual production could compete globally. Today’s manufacturing landscape demands automation, robotics, and advanced technology—areas where India lacks the capital-intensive infrastructure that China developed over decades.

The geopolitical shift toward protectionism and supply chain regionalization further limits the space for new manufacturing entrants. As Rajan noted, trying to follow China’s route now is “like running for a train that already left the station”.

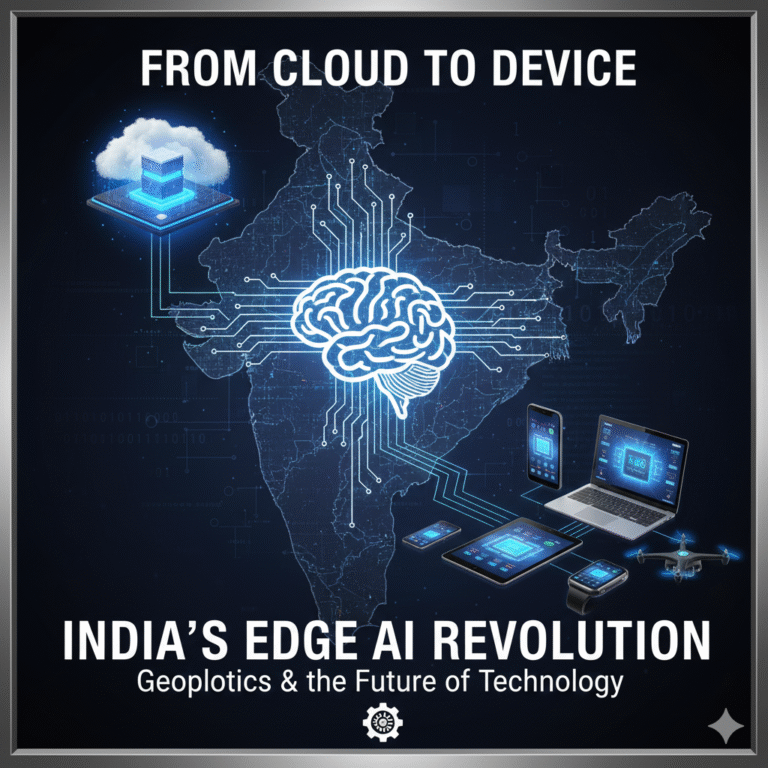

Innovation Linked Incentives: A New Policy Framework

Instead of the current Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, Tantri proposes Innovation Linked Incentives (ILI). This paradigm shift would redirect government resources from supporting manufacturing output to fostering innovation ecosystems.

The ILI framework would focus on:

Talent Clustering: Creating innovation hubs that attract both domestic and international talent, similar to Silicon Valley’s ecosystem approach

Research & Development: Increasing public R&D spending to 1.5% of GDP and establishing DARPA-style mission directorates

Startup Ecosystem: Supporting homegrown startups and high-value sectors rather than assembly operations

Global Talent Attraction: Reversing brain drain through competitive policies and innovation-friendly environments

The Non-Tradable Employment Multiplier Effect

A sophisticated understanding of the innovation-services nexus reveals how high-value tradable sectors drive employment in non-tradable services. When IT professionals, financial analysts, and innovation workers earn higher incomes, they create demand for local services—restaurants, healthcare, education, transportation, and personal services.

This multiplier effect is crucial for inclusive growth. Research shows that growth in tradable services leads to increased employment in non-tradable services, with larger impacts on female workers and small firms. The share of non-tradable services in total non-agricultural employment increased from 55% in the 1990s, demonstrating this sector’s capacity to absorb workers.

Global Competitiveness and Innovation Clusters

India’s innovation potential is already evident in global rankings. Bengaluru has climbed to just outside the top 20 in WIPO’s innovation cluster rankings, with India now boasting four clusters in the top 100. This success came largely through venture capital activity and talent concentration—exactly the ecosystem approach advocated by innovation proponents.

The reverse brain drain phenomenon supports this strategy. Tamil Nadu’s pioneering reverse migration scheme offers globally competitive pay and research grants to attract talent back. Companies report increasing numbers of professionals returning from Silicon Valley to join India’s innovation ecosystem.

Challenges and Implementation Roadmap

Building Innovation Ecosystems requires patience, vision, and sustained policy support. The challenges include:

Infrastructure Development: Creating world-class research facilities and technology parks

Talent Retention: Developing policies to retain and attract global talent

Funding Mechanisms: Establishing patient capital and venture funding ecosystems

Regulatory Framework: Streamlining policies to support innovation and entrepreneurship

The implementation roadmap should focus on:

- Immediate: Redirecting PLI funds toward innovation incentives and research grants

- Short-term: Establishing innovation clusters in major cities with university partnerships

- Medium-term: Creating global talent attraction schemes and startup incubators

- Long-term: Building India into a preferred destination for international innovation investment

The Way Forward: A Balanced Innovation Strategy

The path forward requires strategic rebalancing rather than complete abandonment of manufacturing. The focus should shift toward:

Selective Manufacturing: Supporting high-tech, automated manufacturing that complements innovation ecosystems

Services Integration: Leveraging India’s services strength to support global manufacturing through design, R&D, and support functions

Skill Development: Massive investment in reskilling programs for AI, data science, and emerging technologies

Innovation Infrastructure: Creating world-class research facilities and technology parks with global partnerships

India’s demographic dividend—with 28 years median age and 750 universities—provides a unique opportunity to build innovation-centric growth. The key is channeling this potential through policies that prioritize creativity, research, and high-value services over labor-intensive manufacturing.

+ There are no comments

Add yours