Key Highlights:

- 51 million internal migrants in India (Census 2011) up from 33 million in 2001 with predominantly male migration leaving wives and children behind, affecting over 10.7 million children from rural households requiring educational support

- Father’s migration shows positive association with children’s education through remittance effect with left-behind children scoring higher in achievement tests, but reveals stark gender differentials where sons benefit more robustly than daughters

- 80% migrant children in worksites across seven Indian cities lack access to education while 70% of migrant children in Greater Noida experience school dropout post-migration, highlighting severe access barriers for accompanying children

- Gender-differentiated outcomes show sons experiencing higher reading and arithmetic achievement plus increased education expenditure while daughters gain only in reading skills and investments, revealing persistent son preference in remittance utilization

- Right to Education Act mandates admission for migrant children but implementation gaps persist with 20-30% left-behind children still experiencing enrollment issues and documentation challenges preventing access to education rights

The Scale of India’s Migration-Education Nexus

Internal labour migration in India has reached unprecedented levels, with 51 million people recorded as employment-related migrants in Census 2011, marking a 54% increase from 33 million in 2001. This massive demographic shift represents one of humanity’s largest internal population movements, fundamentally reshaping rural-urban dynamics and creating complex implications for human development outcomes.

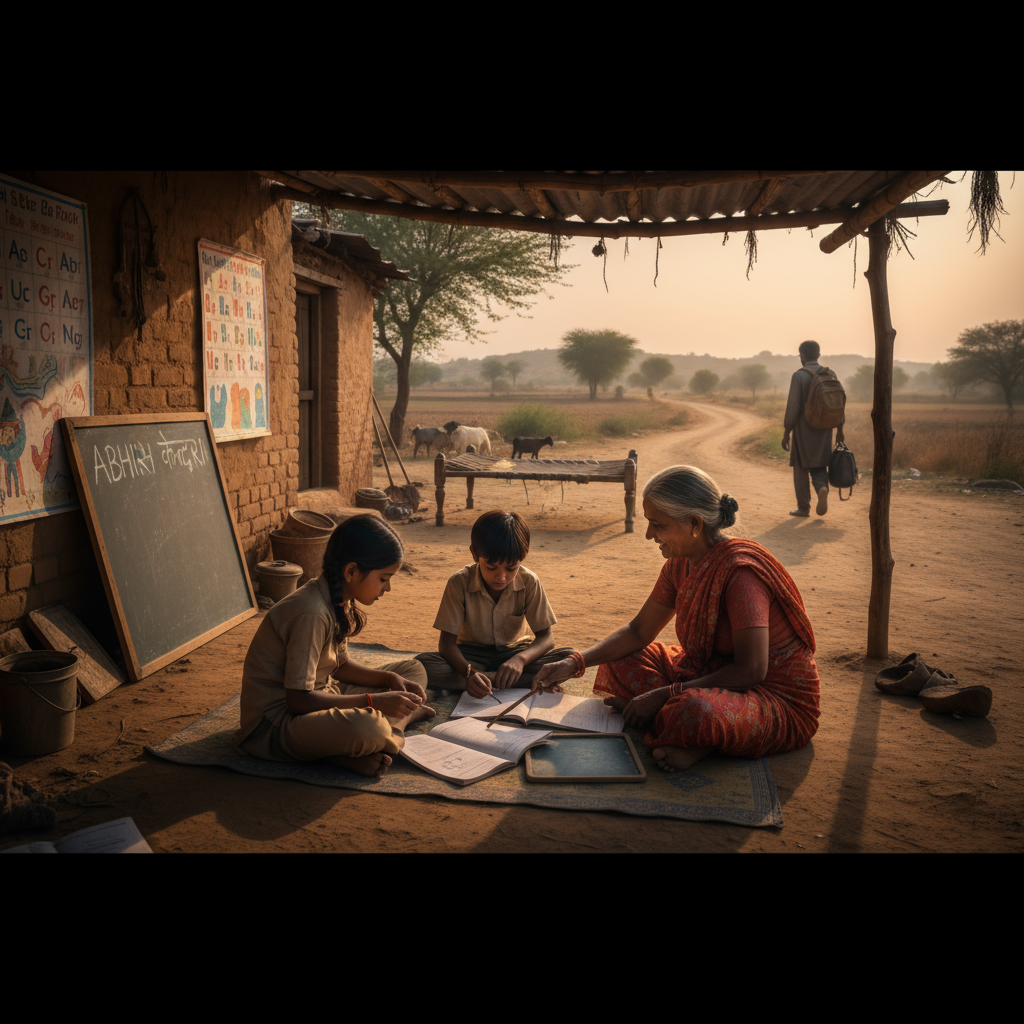

The gendered nature of migration presents particular challenges: predominantly male migrants leave wives and children behind in rural areas while seeking non-farm employment in urban centers. This separation strategy creates two distinct categories of affected children: those left behind in villages under maternal or extended family care, and those accompanying migrants to construction sites and urban destinations.

Understanding this phenomenon becomes crucial for analyzing India’s human development trajectory, particularly as education serves as the primary pathway for breaking intergenerational poverty cycles. The intersection of migration, gender, and education reveals complex dynamics that challenge conventional development assumptions and require nuanced policy responses.

Understanding Internal Migration Dynamics in India

Migration Patterns and Economic Motivations

Rural-urban migration in India is primarily driven by economic constraints and the search for non-farm employment opportunities. Economic Survey data indicates 9 million annual migrants between 2011-2016, with 24% of male migration being employment-related compared to 66.7% of female migration being marriage-related.

Seasonal labor migration serves as a critical household livelihood strategy for coping with poverty, particularly in agriculturally dependent regions. Families adopt this strategy when local employment opportunities are insufficient to meet subsistence needs, forcing temporary separation as a risk-mitigation mechanism.

Educational motivations also drive migration: education ranks as the main reason for internal migration among young men seeking better educational opportunities in urban centers. However, this same motivation creates challenges for the children of migrants who lack similar access to quality education.

Scale of Impact on Children

The magnitude of children affected by parental migration is staggering: millions of children face educational disruption through various pathways. Census data reveals that approximately 454 million migrants existed in India by 2011, rising by 139 million from 315 million in 2001.

Children fall into distinct categories:

Left-Behind Children: Remain in rural areas under maternal or extended family care while fathers migrate for employment

Accompanying Migrant Children: Travel with parents to construction sites, brick kilns, and urban destinations, facing mobility-related educational disruptions

Circular Migration Impact: Children experience repeated disruptions as families engage in seasonal migration cycles, typically lasting 6-8 months annually

Theoretical Framework: Competing Hypotheses from UPSC Perspective

Positive Impact Hypothesis: The Remittance Effect

Economic theory suggests that father’s migration should positively impact children’s education through increased household income via remittances. This income augmentation enables families to invest in educational resources that were previously unaffordable. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih

Mechanisms of Positive Impact:

- Increased educational expenditure on school fees, learning materials, and tuition

- Better school accessibility through improved economic capacity

- Reduced child labor as families can afford to forego children’s economic contributions

- Breaking poverty cycles through enhanced educational opportunities

International evidence supports this hypothesis: Mexican families receiving remittances show higher educational investments, while Philippine data indicates paternal migration leads to increased schooling years.

Negative Impact Hypothesis: The Disruption Effect

Conversely, developmental psychology and family sociology literature suggest father’s absence could negatively impact children’s educational outcomes. Parental supervision, emotional support, and educational guidance are crucial for academic success. idsk

Mechanisms of Negative Impact:

- Reduced parental supervision leading to behavioral problems and poor study habits

- Psychological stress and adjustment challenges affecting concentration and learning capacity

- Increased household responsibilities for children, particularly girls, reducing study time

- Irregular school attendance due to family instability and frequent relocations

Research from China shows left-behind children experiencing higher rates of depression, anxiety, and academic underperformance, supporting the disruption hypothesis.

Empirical Evidence from India Human Development Survey

Overall Impact Findings

Comprehensive analysis using India Human Development Survey data reveals nuanced patterns that support both hypotheses under different conditions. Left-behind children of migrant parents generally score higher in achievement tests relative to children of non-migrants, suggesting the remittance effect dominates.

Key Empirical Findings:

- Father’s current and long-term migration shows positive association with children’s educational outcomes

- Migration contributes to higher education expenditure and increased time spent on educational activities

- Achievement test scores improve across multiple subjects for children of migrants

However, these benefits are not uniformly distributed across gender, age groups, or migration types, revealing important policy implications for targeted interventions.

Gender Differential Outcomes: Critical Analysis

Perhaps the most significant finding concerns gender-differentiated impacts of father’s migration. Sons experience robust remittance effects with higher reading and arithmetic achievement, increased education expenditure, and more time spent on educational activities.

Gender-Specific Outcomes:

Sons (Robust Benefits):

- Significant improvements in both reading and arithmetic scores

- Higher educational expenditure from migrant families

- Increased time allocation for educational activities

- Greater likelihood of continuing education

Daughters (Partial Benefits):

- Higher reading skills but no significant difference in arithmetic achievement

- Increased education investments but limited time allocation changes

- Persistent barriers in household responsibility allocation

This gendered process in remittance utilization reveals persistent son preference despite economic modernization, highlighting structural inequalities that public policy must address.

Subject-Specific Educational Performance Analysis

Achievement Test Variations by Subject

Academic performance varies significantly across subjects based on father’s migration status. Mathematics, Science, and English show particularly pronounced impacts from parental absence, while reading skills demonstrate more consistent improvements across gender lines.

Subject-Specific Patterns:

- Reading comprehension: Generally improves for both genders among children of migrants

- Arithmetic skills: Strong improvement for sons but limited gains for daughters

- Science subjects: Mixed results depending on duration and type of migration

- Language skills: Varies by linguistic environment at destination versus origin

Duration and Timing Effects

Migration duration significantly influences educational outcomes. Long-term migration (across multiple survey waves) shows stronger positive associations than short-term migration, suggesting sustained remittance flows are crucial for educational investments.

Duration Analysis:

- Short-term migration (less than 12 months): Minimal impact on educational outcomes

- Medium-term migration (1-3 years): Moderate positive effects primarily through remittances

- Long-term migration (3+ years): Strongest positive associations but greater psychological costs

Age-Specific Vulnerability reveals that children aged 0-9 versus those aged 10-15 show different responses to paternal migration. Middle school students are more affected than primary school students, while post-15 age groups show higher dropout rates (28%) when compulsory education ends.

Left-Behind vs. Accompanying Migrant Children: Comparative Analysis

Left-Behind Children: Mixed Outcomes

Children remaining in rural areas during father’s migration experience complex trade-offs between economic benefits and supervisory deficits.

Positive Aspects:

- Remittances improving school accessibility and bridging gender gaps in primary education

- Stable educational environment without mobility-related disruptions

- Community support systems providing social capital for educational continuation

Challenges:

- Lack of parental supervision leading to behavioral issues (gaming over studies)

- Psychological impact of family separation affecting mental health and academic focus

- Quality of extended family care varying significantly across households

Better outcomes occur when extended family support is available and community institutions provide supplementary guidance for educational activities.

Accompanying Migrant Children: Severe Access Barriers

Children traveling with migrant parents face far more severe challenges in educational access. 70% of migrant children in Greater Noida experience school dropout post-migration, while 80% of migrant children in worksites across seven Indian cities lack access to education.

Access Barriers:

- Mobility-related disruptions preventing continuous schooling

- Documentation challenges preventing school admission at destination

- Economic necessity forcing 88.9% of families to put children to work instead of school

- Seasonal mobility creating repeated enrollment and dropout cycles

Vulnerability to child labor increases dramatically at construction sites and worksites, with economic pressures forcing 50% of migrant children to work instead of studying.

Socio-Economic and Regional Variations: Analysis

Caste and Class Dimensions

Migration patterns and educational outcomes vary significantly across socio-economic groups. Malnutrition and educational deprivation are higher among socio-economically disadvantaged groups regardless of migration status, but migration can either exacerbate or mitigate these disparities.

Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes show distinct migration patterns with different educational implications. Migration from Empowered Action Group (EAG) states demonstrates unique characteristics requiring targeted policy interventions.

Geographic and Distance Effects

Intra-provincial versus inter-provincial migration creates different educational impacts. Distance affects the frequency of parental visits and quality of supervision, with greater distances associated with larger negative effects on educational continuity.

Migration Type Variations:

- Father-only migration: Moderate effects with remittance benefits partially offsetting supervisory deficits

- Both parents migrating: Largest negative impact due to complete family disruption

- Mother-only migration: No significant impact (rare occurrence in Indian context)

Psychological and Social Dimensions

Mental Health Impact on Educational Outcomes

Stress emerges as a major factor hindering learning abilities and concentration among children of migrants. Father’s absence can lead to psychiatric disorders in children’s personalities, including loneliness, depression, and emotional tension.

Psychological Challenges:

- Separation anxiety affecting academic performance

- Behavioral problems in school settings

- Identity confusion among frequently mobile children

- Social stigma at destination locations affecting self-esteem

International evidence from Philippines shows mixed effects: protective for some age groups but potentially harmful for others, highlighting the importance of age-appropriate interventions.

Social Capital and Guardianship Quality

Extended family care quality becomes crucial in determining educational outcomes for left-behind children. Community support systems can mitigate negative effects of parental absence, while inadequate supervision can exacerbate educational disruptions.

Guardianship Factors:

- Maternal education levels influencing educational prioritization

- Grandparent involvement in academic supervision

- Community institutions providing supplementary support

- Peer group influences in absence of parental guidance

Policy and Institutional Framework in India

Right to Education Act Implementation

The Right to Education Act (2009) mandates free and compulsory education for all children aged 6-14, with specific provisions for migrant children. Local authorities must ensure admission of migrant children with flexible documentation requirements.

RTE Provisions for Migrants:

- Mandatory admission by local authorities regardless of documentation

- National guidelines for flexible admission, transport, and mobile education support

- Seasonal hostels and coordination between sending-receiving districts

- Age-appropriate admission even with delayed enrollment

State-Level Innovations

Progressive states have developed innovative programs to address migrant children’s educational needs:

Gujarat: Seasonal boarding schools and online child tracking systems ensuring continuity across locations

Maharashtra: After-school psychosocial support for children left behind addressing mental health impacts

Tamil Nadu: Textbook provision in multiple languages accommodating diverse migrant populations

Implementation Gaps and Challenges

Despite policy frameworks, significant gaps persist. 20-30% of left-behind children still experience enrollment issues, while documentation challenges prevent access to education rights for many migrant families.

Implementation Challenges:

- Children falling through policy cracks between origin and destination

- Bureaucratic barriers in inter-state coordination

- Limited awareness among migrant families about available rights and services

- Inadequate infrastructure at destination sites for educational support

Multi-Dimensional Policy Recommendations: Framework

Addressing the Guardianship Vacuum

Comprehensive interventions must address the absence of parental supervision while maximizing remittance benefits:

Guardianship Support:

- Expand after-school support programs following Maharashtra’s model

- Strengthen extended family care through community-based interventions

- Regular monitoring of left-behind children’s academic and psychological well-being

- Mobile counseling services for families experiencing separation stress

Improving Educational Access for Migrant Children

Systemic barriers require comprehensive solutions addressing both policy and implementation gaps:

Access Enhancement:

- Simplify documentation requirements for school admission

- Expand seasonal hostels and mobile education units

- Online child tracking systems ensuring continuity across locations

- Bridge courses for children experiencing educational disruptions

Economic Support Mechanisms

Financial interventions should complement rather than substitute for family remittances:

Economic Support:

- Conditional cash transfers linked to school attendance

- Scholarships targeting children of migrant workers

- Subsidies at rural origin more effective than destination for reducing family separation

- Transportation support for maintaining family connections

Gender-Sensitive Interventions

Addressing gender differentials in remittance utilization requires targeted approaches:

Gender Mainstreaming:

- Programs ensuring daughters benefit equally from remittances

- Address son preference in educational investment decisions

- Empower mothers in educational decision-making during father’s absence

- Community awareness programs on gender equality in education

International Comparative Perspectives

China’s Hukou System Parallels

China’s experience with internal migration provides valuable lessons for India. The Hukou system restricts migrants’ access to urban public services, creating similar challenges to India’s documentation barriers.

Chinese Policy Insights:

- Education subsidies at rural origin more effective than destination subsidies

- Family separation reduction requires motivation-focused policies over mobility restrictions

- Left-behind children show higher rates of mental health issues requiring specialized interventions

Philippines and Mexico: Gender Patterns

International research confirms gender-differentiated impacts of father’s migration. Philippine data shows males benefiting more than females from father’s migration, while Mexican evidence indicates age at migration affects outcomes differently.

Global Patterns:

- Age 10-15 shows strongest positive effects from paternal migration

- Remittance effects are more pronounced for sons across multiple countries

- Cultural factors influence gender differentials in educational investment

Economic and Development Implications: Perspective

Poverty-Migration-Education Nexus

Urban poverty in India has crossed 25% with rural migration as a key contributor. Seasonal migration serves as a coping mechanism for poverty but creates educational vulnerabilities that could perpetuate intergenerational poverty.

Development Implications:

- Human capital development requires government intervention beyond remittances

- Educational investment is crucial for breaking poverty cycles

- Sustainable development depends on protecting the next generation’s educational opportunities

Long-Term Human Capital Consequences

The migration-education nexus has profound implications for India’s demographic dividend. Children experiencing educational disruptions today will form tomorrow’s workforce, making current policy interventions critical for future economic growth.

Monitoring and Evaluation Framework

Beyond Conventional Indicators

Effective monitoring requires comprehensive metrics that capture both quantitative and qualitative outcomes:

Enhanced Indicators:

- Psychological health alongside academic performance

- Over-aged schooling as indicator of delayed progression

- School dropout patterns distinguishing temporary from permanent

- Family reunification rates and social cohesion measures

Data and Research Needs

Evidence-based policymaking requires improved data collection and longitudinal research:

Research Priorities:

- Longitudinal studies tracking long-term educational and life outcomes

- Disaggregated data by migration type, duration, child age, and gender

- Documentation of successful interventions for replication

- Cost-benefit analysis of different intervention models

Conclusion: Navigating the Complex Migration-Education Landscape

Father’s migration in India creates a complex web of educational impacts that defies simple categorization as purely beneficial or harmful. The evidence reveals mixed effects: economic benefits through remittances that enable educational investments, counterbalanced by disruptions from parental absence and family separation.

The gender differentials are particularly striking: sons experiencing more robust positive effects than daughters reveals persistent social preferences that policy interventions must address directly. This finding challenges assumptions about migration’s democratizing effects and highlights how traditional gender hierarchies can persist even within modernizing economic strategies.

Left-behind children generally fare better than accompanying migrant children who face severe access barriers, with 80% lacking education access at worksites and 70% experiencing dropout in destinations like Greater Noida. This stark difference underscores the importance of place-based interventions that address distinct challenges faced by different categories of migrant children.

For UPSC aspirants and policymakers, this analysis demonstrates that managing migration’s impact on education requires understanding complex interplay between remittances, family structure, gender dynamics, institutional capacity, and child development needs. Simple solutions like increasing remittances or restricting migration will prove inadequate without comprehensive approaches that address multiple dimensions simultaneously.

Policy success requires moving beyond conventional either-or thinking toward nuanced interventions that maximize remittance benefits while mitigating supervisory deficits. The Right to Education Act provides a strong foundation, but implementation gaps and documentation barriers prevent many children from accessing their constitutional rights.

The challenge represents a critical test for India’s inclusive development aspirations: ensuring no child is left behind despite parental mobility. Success depends on government expanding its role beyond leveraging positive investment effects to alleviating negative guardianship effects through comprehensive support systems.

Sustainable human capital development in 21st century India requires recognizing migration as a permanent feature of economic transformation while building institutions that protect children’s educational opportunities regardless of family mobility patterns. The stakes extend beyond individual families to national development outcomes and India’s ability to harness its demographic dividend for inclusive growth.

+ There are no comments

Add yours