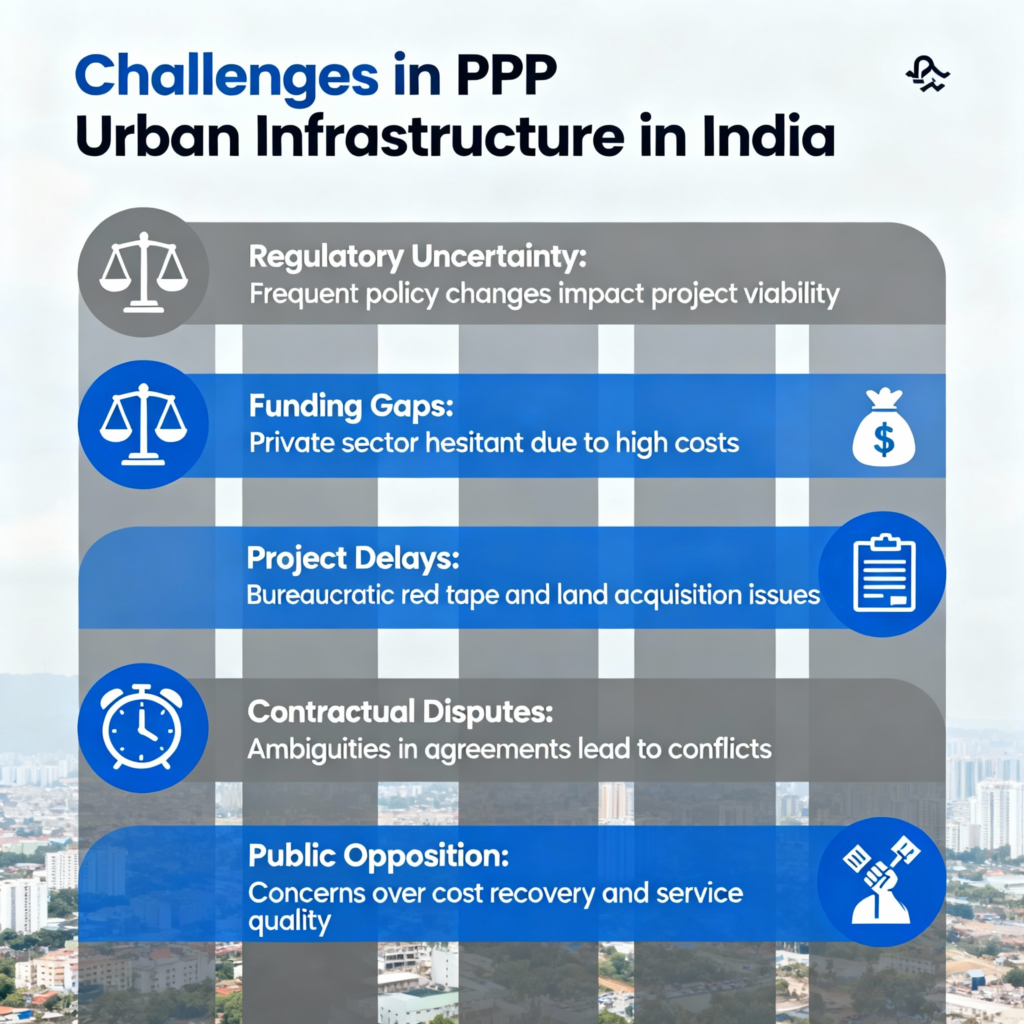

Key Highlights:

- Only 21% of Smart Cities funds utilized through PPP model with 50% of cities unable to implement any PPP projects, questioning the viability of private sector-led urban development

- ₹7 lakh crore estimated investment requirement over 20 years for Smart Cities Mission, with ₹840 billion additional funding needed for urban infrastructure by 2036 according to World Bank projections

- Global technology giants Cisco, IBM, Bosch dominate smart city centers, raising concerns about foreign corporate control over critical urban infrastructure and surveillance systems

- 4% of India’s 834 PPP projects cancelled between 1990-2014, matching global average failure rates while creating hidden debts and fiscal risks for government finances

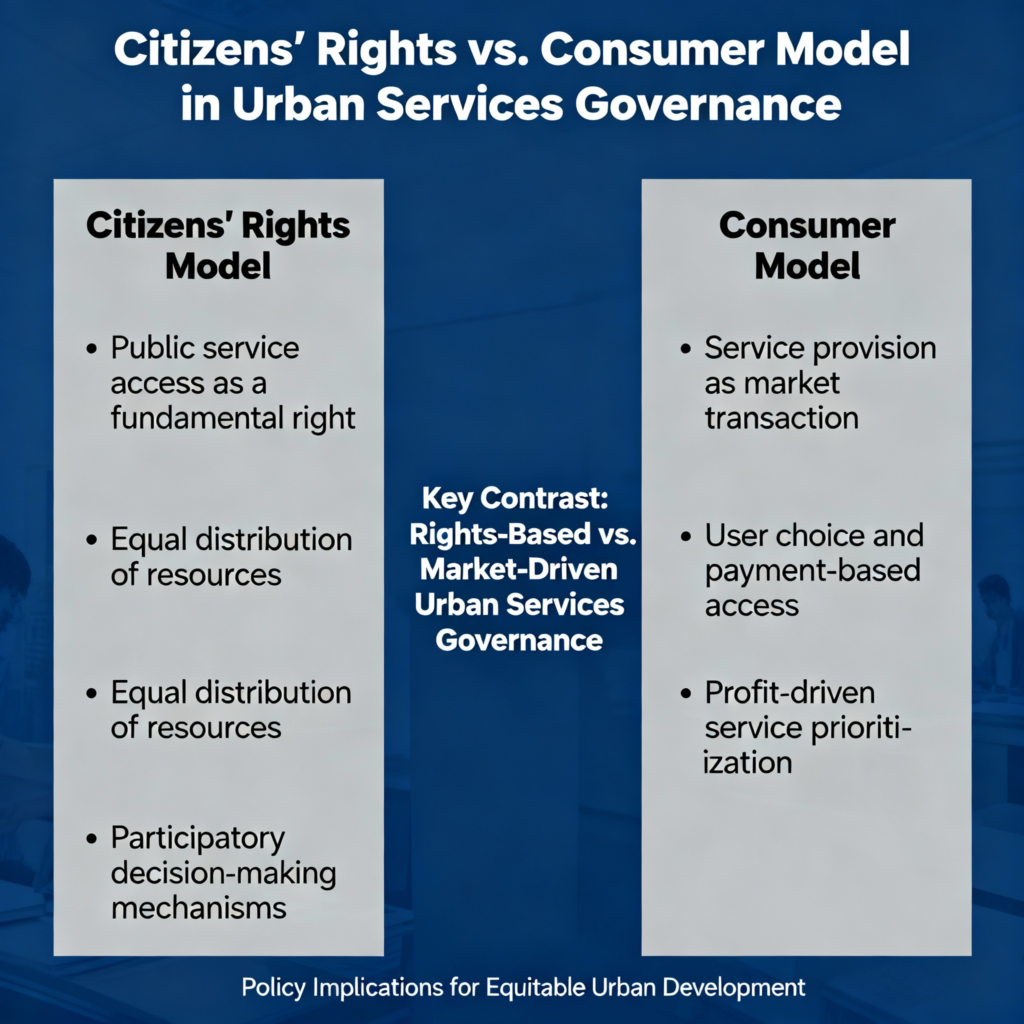

- Citizens transformed from rightsholders to consumers through user charge-based service models, compromising equitable access to essential services like water, health, and sanitation

Introduction: The Smart Cities Mirage

India’s Smart Cities Mission, launched in June 2015 with unprecedented fanfare, promised to transform 100 cities into models of efficient governance, sustainable development, and improved quality of life. The mission’s ambitious scope requires an estimated ₹7 lakh crore investment over 20 years, representing one of the world’s largest urban development initiatives. governancenow

However, beneath the glossy marketing lies a troubling reality: the mission’s heavy reliance on Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) has created a framework that prioritizes corporate profits over citizen welfare. Parliamentary committee reports reveal that half of smart cities have not implemented any PPP projects, while only 21% of allocated funds have been channeled through the PPP model. prsindia

The stakes are enormous: with 600 million Indians expected to live in cities by 2036, representing 40% of the population, urban infrastructure decisions made today will shape India’s development trajectory for generations. The World Bank estimates an additional ₹840 billion requirement for urban infrastructure over the next 15 years, making the choice of delivery models critical for sustainable development.

The Smart Cities Mission represents a paradigmatic shift in Indian urban governance, raising fundamental questions about democratic accountability, social equity, and the role of the state in service delivery.

Understanding PPPs in India’s Urban Context

Defining Public-Private Partnerships

Public-Private Partnerships represent contractual arrangements where private entities assume responsibility for designing, building, financing, operating, and maintaining public infrastructure and services. The PPP Cell, Department of Economic Affairs defines PPPs as arrangements involving majority non-governmental ownership (51% or more) for delivering public assets or services.

Key PPP Characteristics:

- Long-term contracts typically spanning 15-30 years

- Risk transfer from public to private sector

- Performance-based payments linked to service delivery standards

- Private sector capital investment in public infrastructure

Historical Evolution Post-1990s Liberalization

The liberalization era marked a fundamental shift in India’s approach to urban development, moving from state-led provision to market-driven solutions. This transformation reflected broader neoliberal policies emphasizing private sector efficiency and reduced government expenditure.

Pre-1990s Model:

- Direct government provision of urban services

- Municipal corporation management of infrastructure

- Tax-based financing of public services

- Citizens as rightsholders with universal access guarantees

Post-1990s PPP Model:

- Private sector service delivery with government regulation

- User charges and cost recovery mechanisms

- Market-based resource allocation replacing administrative decisions

- Citizens as consumers purchasing services at market rates

Smart Cities Mission PPP Framework

The Smart Cities Mission explicitly promotes PPPs as the preferred delivery model for urban infrastructure. The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs structured the mission to leverage private sector investment while providing government viability gap funding.

Financial Structure:

- Central government contribution: ₹48,000 crore over mission period

- State and ULB matching funds: Equal contribution requirement

- Private sector investment: Expected to provide majority funding through PPPs

- Alternative financing: Municipal bonds, green bonds, and pooled finance mechanisms

SPV Model:

Each smart city establishes a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) as an independent entity managed by government and private stakeholders. However, this structure bypasses traditional democratic governance through elected municipal councils.

Financing Models and Revenue Generation

Diversified Funding Sources

Smart Cities Mission employs multiple financing instruments to mobilize resources beyond traditional government allocations:

Government Sources:

- Central government allocation: ₹500 crore per city over 4 years

- State government matching funds: Equal contribution to central allocation

- 14th Finance Commission transfers: Additional resources for urban local bodies

- Sectoral scheme convergence: Integration with other government programs sesei

Market-Based Instruments:

- Municipal bonds: ₹3,180 crore raised through 33 municipal bond issuances since 2015

- Green bonds: Environmental project financing through capital markets

- Pooled Finance Development Fund: State-level resource aggregation

- Tax Increment Financing: Property value capture for infrastructure funding

User Charge Revolution

The mission fundamentally transforms public service financing through comprehensive user charge systems:

Service Categories:

- Water supply: Per unit consumption charges replacing flat rates

- Waste management: Collection and processing fees for households

- Transport services: Market-based pricing for public transit

- Parking and road use: Congestion pricing and premium facility charges

Impact on Citizens:

This shift transforms citizens from rightsholders to consumers, making essential service access dependent on ability to pay rather than constitutional entitlements. The commodification of basic services creates systematic exclusion of economically vulnerable populations.

Global Context and Corporate Involvement

International Smart City Models

Smart Cities Mission draws inspiration from global implementations in developed countries with vastly different economic and social contexts:

Singapore Model:

- Comprehensive digital integration across all city services

- High per capita income supporting user charges

- Strong state capacity for regulation and oversight

- Homogeneous population with uniform service expectations

Amsterdam Approach:

- Participatory governance with extensive citizen consultation

- Environmental sustainability focus through green technologies

- Social housing integration maintaining affordable access

- EU regulatory framework ensuring consumer protection

Helsinki Experience:

- Open data platforms promoting transparency

- Public sector innovation labs developing in-house capabilities

- Universal basic services maintaining equity alongside efficiency

- Nordic welfare state model ensuring social protection

Transnational Corporate Dominance

Global technology corporations have captured significant portions of India’s smart city investments through strategic partnerships and government contracts:

Major Players:

Cisco Systems:

- Smart city center development in Varanasi, Naya Raipur, and multiple locations

- Networking infrastructure for integrated command and control systems

- Surveillance technology deployment across smart cities

- Technology transfer agreements creating long-term dependencies

IBM Corporation:

- Analytics and AI platforms for city management

- Cloud computing services for municipal data processing

- Watson AI integration for traffic and service optimization

- Smart governance solutions replacing traditional administrative systems

Bosch Group:

- IoT device manufacturing for city-wide sensor networks

- Traffic management systems with intelligent transportation solutions

- Energy management platforms for smart grid implementation

- Security systems integration across urban infrastructure

Indian Corporate Partnerships:

- Larsen & Toubro: Engineering and construction services

- Tech Mahindra: Software development and IT integration

- Shapoorji Pallonji: Infrastructure construction and project management

- Bharat Electronics Limited: Defense-grade communication systems

Institutional Support Network

International financial institutions provide policy guidance and funding support for PPP-based smart city development:

World Bank Group:

- Technical assistance for PPP project structuring

- Policy advisory services on urban finance reform

- Capacity building programs for municipal officials

- Risk mitigation instruments for private sector participation

Asian Development Bank:

- Infrastructure financing through sovereign and non-sovereign windows

- Knowledge sharing on regional smart city experiences

- Climate-resilient infrastructure promotion

- Private sector development support

Bilateral Cooperation:

- US-India cooperation: Technology transfer and investment facilitation

- German technical assistance: Urban planning and environmental solutions

- Singapore partnership: Smart governance and digital systems

- French collaboration: Sustainable transport and energy systems

Critical Evaluation of PPP Performance

Parliamentary Committee Findings

Standing Committee on Housing and Urban Affairs investigations reveal systematic underperformance of the PPP model in Smart Cities Mission:

Financial Performance:

- Only 21% of smart city funds utilized through PPP mechanisms

- 50% of cities unable to implement any PPP projects

- 207 PPP projects worth ₹2,10,794 crore approved but only ₹707 crore spent

- 6% execution rate of approved PPP project costs

Project Completion Challenges:

- 400 projects worth ₹22,814 crore missed December 2023 deadlines

- Mission extended multiple times from original 2020 completion target

- Frequent CEO transfers disrupting project continuity

- Land acquisition delays and legal challenges stalling implementation

World Bank Assessment of PPP Failures

World Bank’s comprehensive evaluation of PPP programs reveals structural problems with the model globally and specifically in India:

Performance Indicators:

- PPP projects significantly less successful than IFC direct investments

- Complex project design leading to implementation delays

- Unrealistic timeframes forcing frequent renegotiations

- 4% cancellation rate for Indian PPP projects matching global averages

Implementation Challenges:

- Overly complex project structure exceeding institutional capacity

- Institutional fragmentation among multiple government agencies

- Limited accountability mechanisms for performance monitoring

- Poor risk allocation between public and private partners

Financial Risks:

- High transaction costs for project development and monitoring

- Hidden government liabilities through guarantees and support mechanisms

- Renegotiation pressures increasing public sector financial exposure

- Limited private sector risk transfer despite PPP objectives

Urban Water PPP Case Studies

World Bank analysis of five recent PPP initiatives in Indian cities demonstrates systematic failures in water sector PPPs:

Project Outcomes:

- Khandwa, Nagpur, Aurangabad, Mysore, Latur: All projects failed to meet service delivery targets

- Daily water supply promises remained unfulfilled despite PPP implementation

- 100% coverage commitments not achieved in any project

- Customer service improvements minimal or non-existent

Structural Problems:

- No focus on capital investment efficiency with public funds availability reducing incentives for optimization

- Weak performance monitoring with limited recourse for poor service delivery

- Risk sharing imbalances with standard clauses varying significantly between contracts

- Communication failures with no stakeholder engagement or opinion research

Revenue Model Contradictions

PPP revenue structures create fundamental conflicts between private profit maximization and public service accessibility:

User Charge Dependencies:

PPPs rely on user charges for revenue generation, creating direct competition with municipal bond financing that also depends on city revenue streams. This zero-sum relationship constrains both PPP viability and municipal borrowing capacity.

Service Delivery Priorities:

- Private operators prioritize profitable customers over universal access

- Cross-subsidization mechanisms weak or absent in PPP contracts

- Service quality varies based on payment capacity rather than need

- Public interest objectives subordinated to commercial viability

Governance and Democratic Accountability Crisis

SPV Model vs Constitutional Framework

Smart Cities Mission’s Special Purpose Vehicle structure conflicts with constitutional provisions for urban local self-governance:

74th Amendment Implications:

The 74th Constitutional Amendment Act, 1992 mandates elected municipal councils as institutions of local self-government with constitutional powers over urban planning and service delivery. SPV structures bypass elected representatives, creating parallel governance systems without democratic legitimacy.

Accountability Gaps:

- SPV board composition includes private sector representatives with commercial interests

- Decision-making processes lack public participation mechanisms

- Financial decisions made without municipal council approval

- Performance monitoring conducted by SPV management rather than elected representatives

Transformation of Citizenship

PPP-based service delivery fundamentally alters the relationship between state and citizen:

Rights vs Consumer Model:

Constitutional Rights Framework:

- Articles 19, 21 guarantee fundamental rights to life and liberty

- Article 243W provides constitutional status to urban local bodies

- Directive Principles mandate state provision of essential services

- Citizens as rightsholders with entitlements to basic services

Market Consumer Model:

- Services priced at market rates based on cost recovery principles

- Access dependent on ability to pay rather than constitutional entitlements

- Quality varies by price point creating tiered service systems

- Citizens as consumers with market-based relationships to service providers

Regulatory Capture and Corporate Influence

Corporate involvement in Smart Cities governance creates systematic bias toward commercial interests over public welfare:

Technology Vendor Lock-in:

- Proprietary systems from Cisco, IBM, Bosch create long-term dependencies

- Switching costs prohibitive for cities seeking alternative solutions

- Contract terms favor vendor interests over municipal flexibility

- Technology standards set by corporate partners rather than public agencies

Policy Influence Mechanisms:

- Technical advisory committees dominated by corporate representatives

- Training programs conducted by vendors shaping official perspectives

- Pilot project funding creating demonstration effects for broader adoption

- International best practice narratives promoting vendor solutions

Social Impact and Equity Concerns

Exclusion Through User Charges

PPP-based service delivery systematically excludes economically vulnerable populations through market-based access mechanisms:

Water Service Impacts:

- Per unit pricing replaces flat rate or subsidized access

- Connection deposits and monthly charges beyond poor household budgets

- Disconnection policies for non-payment creating humanitarian crises

- Quality tiers with premium services for paying customers

Urban Transport Changes:

- Market-based pricing for public transit increases commuting costs

- Premium services for higher-income users while basic services deteriorate

- Route optimization based on profitability rather than social need

- Accessibility features limited to commercially viable corridors

Displacement and Gentrification

Smart Cities projects often require land acquisition and redevelopment that displaces existing communities:

Project Impacts:

- Street vendor relocation from prime commercial areas

- Slum clearance for infrastructure development without adequate rehabilitation

- Property tax increases following area-based development causing resident displacement

- Commercial gentrification changing neighborhood character and affordability

Compensation Mechanisms:

- Land acquisition compensation often inadequate for urban resettlement costs

- Livelihood restoration programs poorly implemented or absent

- Community consultation processes perfunctory without meaningful participation

- Grievance redressal systems weak or inaccessible to affected populations

Alternative Models and Policy Recommendations

Strengthening Public Sector Capacity

Rather than defaulting to PPP models, India can strengthen municipal capacity for direct service delivery:

Institutional Development:

- Dedicated urban cadre with technical expertise in infrastructure management

- Municipal engineering colleges providing specialized training for city officials

- Inter-city learning networks facilitating knowledge sharing and best practice exchange

- Performance management systems linking official incentives to service delivery outcomes

Financial Capacity Building:

- Property tax reform increasing municipal revenue through better assessment and collection

- Municipal bond markets development with credit rating and investor education

- Pooled finance mechanisms enabling smaller cities to access capital markets

- Central and state transfers based on performance indicators rather than political allocation

Participatory Governance Models

Democratic participation can be strengthened through institutional innovations that engage citizens in urban planning and service delivery:

Citizen Engagement Mechanisms:

- Ward sabhas with constitutional powers over local planning and budget allocation

- Public hearings for major infrastructure projects with binding consultation requirements

- Citizen monitoring committees for service delivery quality assessment

- Digital participation platforms enabling broader citizen input in urban planning

Transparency and Accountability:

- Open data policies for municipal finances, contracts, and performance indicators

- Social audits of public projects conducted by citizen groups

- Right to Information implementation ensuring access to government documents

- Public interest litigation mechanisms for challenging urban development decisions

Hybrid Financing Models

Mixed financing approaches can mobilize private resources while maintaining public control over service delivery:

Public Finance Innovation:

- Municipal green bonds for environmentally sustainable infrastructure

- Tax increment financing capturing property value increases from infrastructure investment

- Land value capture mechanisms funding public transport and affordable housing

- Development charges on private projects funding public infrastructure

Regulated Private Participation:

- Competitive contracting for specific services with strong performance standards

- Management contracts maintaining public ownership while accessing private expertise

- Joint ventures with majority public control and clear social objectives

- Utility regulation models ensuring affordable access while allowing cost recovery

International Lessons and Best Practices

European Social Market Models

European cities demonstrate how market mechanisms can be integrated with social protection for equitable urban development:

Vienna Social Housing:

- Public housing provision for 60% of residents ensuring affordable accommodation

- Cross-subsidization from commercial developments funding social housing

- Long-term planning with 100-year development strategies

- Quality standards maintaining high-standard public housing

Copenhagen Climate Adaptation:

- Public investment in climate resilience infrastructure

- Citizen participation in neighborhood-level planning

- Environmental regulation ensuring private development contributes to climate goals

- Public-public partnerships between municipal agencies and public utilities

Developing Country Innovations

Cities in the Global South offer relevant models for Indian urban development:

Medellín Urban Acupuncture:

- Strategic public investment in marginalized neighborhoods

- Integrated urban projects combining transport, education, and public space

- Community participation in project design and implementation

- Public architecture as catalyst for social transformation

Curitiba Integrated Planning:

- Bus rapid transit system with public ownership and operation

- Land use planning integrated with transport development

- Green space preservation through regulatory mechanisms

- Citizen education campaigns promoting sustainable behavior

Conclusion: Reclaiming Cities for Citizens

India’s Smart Cities Mission stands at a critical juncture. The evidence is overwhelming: PPP-based urban development has systematically failed to deliver on its promises of efficiency, innovation, and improved service delivery. With only 21% of funds flowing through PPP mechanisms and 50% of cities unable to implement any PPP projects, the model’s inadequacy is undeniable.

The human cost is enormous: millions of urban citizens are being transformed from rightsholders to consumers, their access to basic services increasingly dependent on ability to pay rather than constitutional entitlements. This commodification of urban governance threatens the democratic foundation of Indian cities and exacerbates inequality in rapidly growing urban areas.

For UPSC aspirants and governance professionals, this crisis offers crucial lessons about the limits of market-based solutions for public service delivery. Understanding these dynamics becomes essential for evidence-based policy making that prioritizes public interest over corporate profits.

The alternative path is clear: strengthen public sector capacity, enhance democratic participation, and develop innovative financing mechanisms that mobilize private resources while maintaining public control. Cities like Vienna, Medellín, and Curitiba demonstrate that public-led urban development can deliver superior outcomes for citizens and environment.

The choice before India is stark: continue down the path of corporate capture through failed PPP models, or reclaim urban governance for the people who live in cities. The ₹7 lakh crore investment in Smart Cities Mission represents a historic opportunity to build inclusive, sustainable, and democratic cities.

The time for course correction is now. Indian cities deserve better than becoming cash cows for multinational corporations. They deserve to be homes for all citizens, not just those who can afford to pay.

+ There are no comments

Add yours