Key Highlights

- Constitutional Landmark: Puttaswamy judgment (2017) by nine-judge Supreme Court bench declared privacy as fundamental right under Article 21, overruling previous decisions and establishing “intrinsic to life and personal liberty” principle

- DPDPA 2023 Implementation: Digital Personal Data Protection Act passed August 2023 with ₹250 crore maximum penalties, awaiting operational guidelines and Data Protection Board establishment for comprehensive enforcement

- FRT Surveillance Expansion: Automated Facial Recognition System (AFRS) deployed across 15+ states for policing without regulatory framework, raising mass surveillance concerns and democratic accountability questions

- Global Standards Alignment: DPDPA balances between EU GDPR strict consent requirements and US sectoral approach, incorporating data localization, cross-border restrictions, and innovation-friendly provisions

- Enforcement Gap Challenge: Despite constitutional recognition and legislative framework, weak implementation, absence of independent authority, and coordination challenges between central-state agencies limit practical privacy protection

Constitutional Foundation: The Puttaswamy Revolution

The landmark Justice K.S. Puttaswamy judgment delivered on August 24, 2017, by a nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court represents a watershed moment in Indian constitutional jurisprudence. The 547-page unanimous judgment categorically declared that “privacy is intrinsic to life and personal liberty” and is inherently protected under Article 21 of the Constitution. centurylawfirm

This historic decision overruled two previous Supreme Court judgments – the eight-judge bench in M.P. Sharma case and the six-judge bench in Kharak Singh case – which had denied constitutional status to privacy rights. The 2017 judgment elevated privacy from a mere policy consideration to a fundamental constitutional protection available to all individuals, not just Indian citizens.

Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, writing for the majority, emphasized that privacy enables free expression, protects against surveillance, and forms the bedrock of democratic discourse and personal development. The judgment linked privacy to constitutional values of dignity, autonomy, and liberty, establishing it as “essential ingredient” of other fundamental freedoms under Part III of the Constitution.

Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023: Legislative Framework

Comprehensive Legal Structure

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA) 2023, passed by Parliament in August 2023 and receiving Presidential assent on August 11, represents India’s first comprehensive data protection legislation. The Act will replace the existing patchwork of IT Rules 2011 and sectoral regulations with a unified framework for digital data protection. Iw

Key provisions include strict consent requirements, data principal rights (equivalent to data subjects), data fiduciary obligations (equivalent to data controllers), and significant penalties up to â‚ą250 crore for non-compliance. The Act introduces a special category of “Significant Data Fiduciaries” with enhanced obligations including Data Protection Impact Assessments and Data Protection Officers.

DPDPA’s scope covers digital personal data processing within India and processing outside India if offering goods/services to Indian users. Unlike GDPR, the Act excludes non-automated personal data, offline data, and personal data existing for 100+ years.

Implementation Challenges and Timeline

No operational timeline has been officially announced, though stakeholders expect phased implementation within 6-12 months after Data Protection Board establishment and subordinate rules formulation. The Ministry of Electronics and IT published DPDP Rules on January 3, 2025, providing operational framework for compliance.

Critical gaps include absence of the Data Protection Board of India (DPB) – the primary enforcement authority – and detailed procedural guidelines for grievance redressal, data breach notifications, and international data transfers. The Act delegates significant powers to the Central Government through rules and exemptions.

Compliance preparation requires organizations to assess current data practices, implement consent mechanisms, establish data security measures, and prepare for individual rights fulfillment.

Facial Recognition Technology: The Surveillance Dilemma

Widespread Deployment Without Regulation

Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) deployment across India has expanded rapidly since 2019 without comprehensive regulatory framework, raising serious concerns about mass surveillance and democratic accountability. The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) launched the Automated Facial Recognition System (AFRS) project in June 2019 to “modernize policing” and “criminal identification”. techpolicy

State-level and city-level FRT projects have emerged in Hyderabad, Chennai, Chandigarh, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar, Delhi, Jammu & Kashmir, Odisha, Haryana, and other regions. Hyderabad’s FRT and CCTV projects became the focus of Amnesty International’s “Ban the Scan” global campaign.

Original AFRS proposal envisioned two key uses: field officers could photograph suspects for FRT analysis and integration with nationwide CCTV networks for real-time mass surveillance. Though the government ostensibly dropped CCTV integration following civil society concerns, scene-of-crime images/videos were added as input data, suggesting potential conflicts.

Privacy and Accuracy Concerns

FRT’s inherent capabilities enable “covert and remote mass authentication” without notice or direct interaction, designed for universal surveillance rather than targeted investigations. Significant privacy and free speech concerns arise from any law enforcement deployment of this technology.

Accuracy limitations include misidentification, particularly across racial and gender demographics, creating risks of wrongful identification and discriminatory enforcement. IP cameras used in many FRT deployments are “more susceptible” to unauthorized break-ins and hacking compared to closed-circuit networks.

Regulatory oversight remains sparse despite widespread deployment, with no comprehensive legal framework governing FRT or AI technologies in India. Private companies developing FRT systems through government tenders bear moral and ethical responsibility for developing non-intrusive technology with maximum security safeguards

EU GDPR vs Indian DPDPA

European Union’s GDPR serves as the “global gold standard” with strict consent-based processing, comprehensive individual rights, and extraterritorial jurisdiction. Maximum penalties under GDPR reach 4% of global annual turnover or €20 million, whichever is higher. prsindia

DPDPA’s approach balances privacy protection with innovation-friendly regulation, featuring simplified consent mechanisms and flexible processing grounds. Key differences include DPDPA’s focus on digital data only, exclusion of sensitive data categories, and different territorial scope.

Consent frameworks differ significantly: GDPR requires explicit consent for most processing, while DPDPA allows legitimate uses without consent including voluntary data sharing, state processing for permits/licenses, and research purposes.

China and USA Models

China’s approach prioritizes data sovereignty and state security through Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) and Data Security Law (DSL), emphasizing government control over individual rights. Cross-border data transfers face strict restrictions and security assessments.

United States follows a sectoral approach with less stringent comprehensive privacy law but strong sector-specific regulations like HIPAA (health), COPPA (children), and state-level California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). Federal privacy legislation remains fragmented compared to comprehensive approaches.

India’s model attempts to balance individual privacy rights with state interests and economic development, avoiding both China’s authoritarian approach and America’s fragmented system

Emerging Technologies and Privacy Challenges

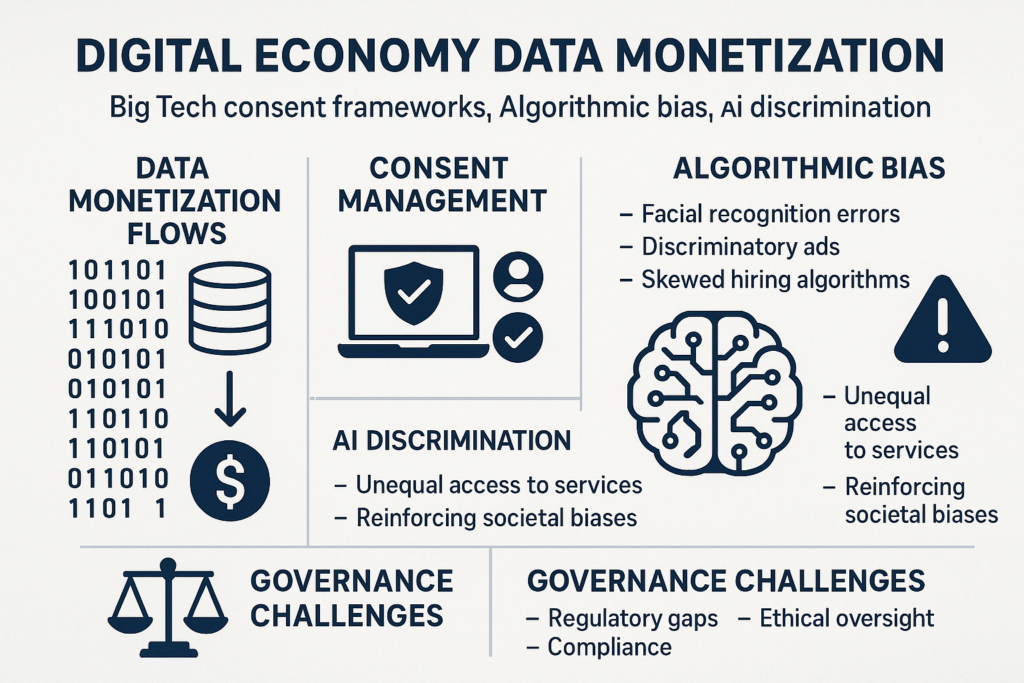

AI and Algorithmic Bias

Artificial Intelligence systems and algorithmic decision-making present unprecedented challenges for privacy protection, particularly regarding profiling, discrimination, and automated decisions. Machine learning algorithms can infer sensitive information from seemingly innocuous data, creating new categories of privacy violations.

Algorithmic bias in AI systems can perpetuate and amplify existing discrimination against marginalized communities, women, and minority groups. Lack of transparency in algorithmic decision-making makes it difficult for individuals to understand or challenge automated decisions affecting them.

DPDPA’s provisions for automated decision-making remain limited, potentially inadequate for addressing complex AI-driven privacy violations. Future regulations may need specific provisions for AI governance, algorithmic auditing, and explainable AI requirements.

Biometric Data and Health Information

Aadhaar system’s 12-digit biometric identification affects over 1.3 billion residents, creating the world’s largest biometric database with significant privacy implications. Post-Puttaswamy regulations have restricted Aadhaar usage, but concerns persist about data security and function creep.

Ayushman Bharat and digital health initiatives collect vast amounts of sensitive health data, requiring robust protection against misuse and unauthorized access. Health data sensitivity demands enhanced security measures and strict consent protocols.

Deepfakes and synthetic media create new privacy threats by enabling impersonation and identity theft at unprecedented scale. Intersection of privacy and security concerns requires comprehensive policy responses.

Administrative and Enforcement Challenges

Federal Coordination Issues

Central agencies (Intelligence Bureau, National Investigation Agency) and state police forces face coordination challenges in privacy-sensitive investigations. Jurisdictional ambiguity between central and state authorities can undermine consistent privacy protection.

Lack of independent Data Protection Authority with strong enforcement powers represents a critical gap in privacy governance. Data Protection Board establishment under DPDPA will determine practical effectiveness of privacy rights enforcement.

Balancing law enforcement needs with individual freedoms requires clear guidelines, judicial oversight, and accountability mechanisms. Proportionality tests established in Puttaswamy provide framework but implementation remains challenging.

Implementation Gaps

Five years after Puttaswamy judgment, many promises remain unfulfilled due to weak implementation, limited awareness, and insufficient institutional capacity. Constitutional recognition has not translated into practical protection for most citizens.

Surveillance practices continue expanding despite constitutional privacy rights, suggesting disconnect between legal principles and administrative practices. FRT deployment without regulatory framework exemplifies this implementation gap.

Civil society concerns about “surveillance state” development conflict with national security arguments, requiring democratic dialogue and transparent governance.

Economic and Strategic Implications

Digital Economy and Innovation

Data as “new oil” drives AI, fintech, ed-tech, and health-tech sectors, making privacy protection essential for consumer trust and Digital India success. Strong privacy frameworks can enhance competitiveness by building user confidence in digital services. hstalks

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) flows increasingly depend on robust data protection and cybersecurity frameworks. European and American companies prioritize privacy-compliant jurisdictions for data processing operations.

Data localization requirements in DPDPA may conflict with global trade competitiveness but enhance domestic data sovereignty. Cross-border data flow restrictions require careful balancing of security and economic interests.

Startup and Innovation Impact

Privacy compliance costs can burden startups and small businesses, potentially stifling innovation if implementation becomes overly complex or expensive. Simplified compliance procedures for smaller entities may be necessary.

Trust-based business models in digital economy depend on transparent privacy practices and user control over personal data. Privacy-by-design approaches can create competitive advantages for Indian companies.

Global expansion of Indian digital companies requires compliance with multiple privacy regimes, making strong domestic framework a foundation for international growth.

Ethical and Civil Society Perspectives

Positive vs Negative Equality

Positive equality approach views data protection as empowering vulnerable groups and preventing discrimination through algorithmic bias prevention and inclusive design. Privacy rights protect marginalized communities from discriminatory profiling.

Negative equality concerns focus on potential innovation stifling through excessive data control and regulatory burden. Balance between protection and innovation requires nuanced policy approaches.

Collective good perspective treats privacy as foundation of democracy, not just individual liberty, emphasizing social benefits of privacy protection for democratic discourse and social cohesion.

Democratic Values and Surveillance State Concerns

Surveillance state concerns reflect fears about government overreach and democratic backsliding through mass surveillance technologies. FRT deployment without democratic oversight exemplifies these concerns.

National security arguments for surveillance must be balanced against fundamental rights through proportionality tests, judicial review, and parliamentary oversight. Transparent governance essential for maintaining public trust.

Civil society engagement in privacy governance ensures democratic accountability and prevents authoritarian technology use. Public participation in policy-making strengthens democratic legitimacy.

Future Directions and Recommendations

Strengthening Legal Framework

Comprehensive AI governance legislation needed to address algorithmic bias, automated decision-making, and emerging technology challenges. Current legal framework inadequate for AI-era privacy protection.

Independent regulatory authority with strong enforcement powers essential for effective privacy protection. Data Protection Board must be truly independent and adequately resourced for meaningful oversight.

Sectoral guidelines for healthcare, finance, education, and other sensitive sectors needed to complement general privacy framework. Industry-specific privacy requirements can enhance protection.

Technology Governance

Mandatory privacy impact assessments for government technology projects, particularly surveillance systems like FRT, can prevent harmful deployments. Democratic oversight of technology procurement essential.

Privacy-by-design requirements for all government and commercial systems can embed protection at system architecture level. Technical standards and certification programs can ensure compliance.

Transparency reporting by government agencies and private companies about data processing activities, surveillance operations, and privacy compliance can enhance accountability.

Capacity Building and Awareness

Digital literacy programs must include privacy education to empower citizens to exercise their rights effectively. Public awareness of privacy rights remains critically low.

Judicial training on privacy law and technology issues essential for consistent and informed court decisions. Legal profession needs capacity building in privacy law.

Civil society organizations play crucial role in privacy advocacy, public education, and government accountability. Support for privacy organizations strengthens democratic governance.

International Cooperation and Diplomacy

Global Standards and Harmonization

WTO e-commerce negotiations on cross-border data flows require India to balance domestic privacy protection with international trade commitments. Strategic participation in global governance forums essential.

Bilateral and multilateral data sharing agreements must include robust privacy protections and democratic oversight mechanisms. Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties need privacy safeguards.

Global South cooperation on privacy governance can create alternative models to Western and Chinese approaches. India’s leadership in democratic privacy governance can influence international standards.

Technology Transfer and Innovation

International collaboration on privacy-preserving technologies, secure multiparty computation, and differential privacy can enhance protection while enabling innovation. Research partnerships benefit global privacy ecosystem.

Standards organizations participation ensures Indian interests in global technology standards. Privacy engineering standards need Indian contribution and adoption.

Capacity building assistance to other developing countries in privacy governance strengthens India’s soft power and creates aligned partners in international forums.

Conclusion

India’s data privacy journey from the landmark Puttaswamy judgment to the comprehensive DPDPA 2023 represents a remarkable transformation in constitutional jurisprudence and legislative framework, establishing privacy as a fundamental right while balancing innovation with protection. The nine-judge Supreme Court bench’s unanimous declaration that privacy is “intrinsic to life and personal liberty” under Article 21 created a solid constitutional foundation for digital rights protection in India.

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023, with its â‚ą250 crore maximum penalties and comprehensive framework, positions India among nations with robust privacy legislation, though implementation challenges and regulatory gaps remain significant. The absence of an operational Data Protection Board and detailed procedural guidelines highlights the critical need for swift institutional development and clear enforcement mechanisms.

Facial Recognition Technology deployment across 15+ states without adequate regulatory oversight exemplifies the tension between technological advancement and privacy protection, raising legitimate concerns about mass surveillance and democratic accountability. The lack of comprehensive FRT regulation demonstrates the urgent need for technology-specific governance frameworks that balance security needs with constitutional rights.

Global comparisons reveal India’s balanced approach between EU’s strict GDPR standards and America’s sectoral model, incorporating innovation-friendly provisions while maintaining essential protections. This middle path could position India as a leader in democratic privacy governance for the Global South, offering an alternative to both Western and Chinese models.

Emerging challenges from AI, algorithmic bias, biometric systems, and deepfakes require proactive policy responses that current frameworks may inadequately address. The intersection of privacy, security, and innovation demands nuanced approaches that protect rights while enabling technological progress.

Implementation gaps between constitutional recognition and practical protection highlight the critical importance of institutional capacity, enforcement mechanisms, and public awareness. Five years after Puttaswamy, many promises remain unfulfilled, underscoring the need for sustained commitment to translating legal principles into lived reality for Indian citizens.

Economic implications of privacy protection extend beyond compliance costs to competitive advantages in global markets, enhanced FDI attractiveness, and stronger foundation for Digital India initiatives. Trust-based business models in the digital economy depend on robust privacy frameworks and transparent practices.

Democratic values and civil society engagement remain essential for preventing surveillance state development while ensuring legitimate security needs are addressed transparently. The balance between individual privacy and collective security requires continuous democratic dialogue and institutional accountability.

Future directions must focus on strengthening legal frameworks for emerging technologies, establishing truly independent regulatory authorities, building institutional capacity, and fostering international cooperation on privacy standards. Success in these areas will determine whether India can realize the transformative potential of digital privacy rights while maintaining democratic governance and technological innovation.

The journey from Puttaswamy to practical privacy protection is far from complete, requiring sustained effort from government, civil society, private sector, and citizens to build a privacy-respecting digital ecosystem that serves both individual rights and national development. India’s experience in navigating this complex landscape will influence global privacy governance for decades to come.

đź“Ś Practice Questions

Mains (10–15 marks)

- Right to Privacy is not an absolute right. Critically evaluate in light of recent data protection debates in India.

- Discuss the challenges in balancing innovation, economic growth, and citizens’ data privacy in the digital economy.

- Compare India’s data protection framework with the EU’s GDPR. What lessons can India learn?

+ There are no comments

Add yours