The Ground Beneath the Conflict: What’s Really at Stake

In the shadow of Myanmar’s prolonged political crisis, a quieter but more potent battle is unfolding over the world’s rarest—and most critical—resources.

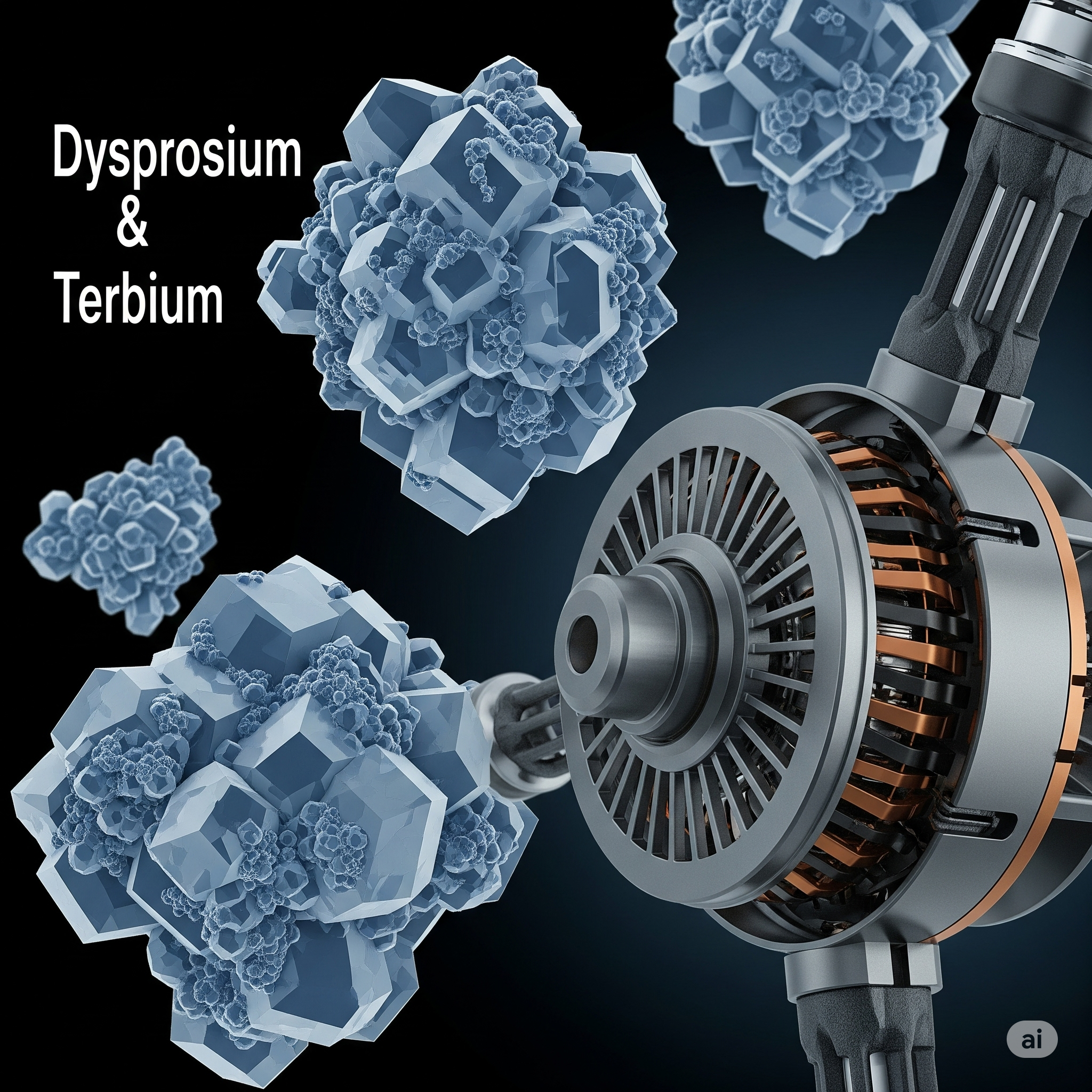

China, which already dominates the global rare-earth metals market, is scrambling to maintain access to heavy rare earths such as dysprosium and terbium, which are essential for technologies like:

- Electric vehicles

- Wind turbines

- Guided missiles

- Smartphones and satellites

And much of that supply comes not from China itself, but from neighboring Myanmar, specifically Kachin State—a rugged, rebel-controlled region rich in mineral wealth.

As rebel advances disrupt the mining and smuggling networks that funnel these minerals into China, Beijing is responding not with troops—but with diplomatic threats, militia proxies, and raw economic pressure. This is not just about mining—it’s about global power, tech dominance, and strategic leverage.

⛏️ What Are Rare Earths and Why Do They Matter?

Rare earth elements (REEs) are a group of 17 chemically similar elements, with heavy rare earths like dysprosium (Dy) and terbium (Tb) being the most valuable and difficult to mine.

🧪 Why They’re Crucial:

- Dysprosium: Improves the heat resistance of magnets in EVs and military jets

- Terbium: Used in solid-state devices, sonar systems, and green lasers

- Neodymium + Praseodymium: Common in EV motors and wind turbines

As the global green transition accelerates, demand for these elements is exploding. Yet over 80% of global processing is controlled by China, giving it enormous economic and strategic leverage.

📦 China’s Rare Earth Strategy: Dependence Disguised as Dominance

Despite appearing as a resource-rich powerhouse, China imports nearly 50% of its heavy rare-earth raw ore from Myanmar. These raw materials are smuggled or exported semi-legally into southern China, where they are refined and processed in vast industrial facilities.

This dependency is a strategic vulnerability—one China is now fighting to plug.

🎯 Beijing’s Tactics:

- Leverage over rebel groups: Pressuring the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) to halt its offensive

- Backing local militias: Arming pro-China militia networks in other parts of Myanmar to secure mining access

- Weaponizing trade: Threatening rare-earth export bans if mining disruptions continue

- Rapid diversification: Boosting stockpiles and investing in processing tech for lower-grade ores at home

This is a clear example of geo-economic statecraft: using economic tools to achieve geopolitical goals.

🔫 Enter the Rebels: Who Are the Kachin Independence Army (KIA)?

The Kachin Independence Army, one of Myanmar’s most powerful ethnic rebel groups, has waged war for decades against the military junta for autonomy and control over resource-rich territories.

In recent months, the KIA has:

- Seized key mining zones in Kachin State

- Cut off transport routes to China

- Threatened mining operations tied to China-backed entities

For Beijing, this is not just about regional instability—it’s about strategic disruption to its tech and defense industries. It has reportedly:

- Sent emissaries to warn KIA leaders

- Pressured the Myanmar junta to clamp down on rebel offensives

- Enabled pro-Beijing militias to reopen alternate mining routes in Shan and Wa states

🧭 The Myanmar Map of Minerals: A High-Stakes Geo-Grid

| Region | Group in Control | Resource | Strategic Importance to China |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kachin State | KIA (Rebels) | Dysprosium, Terbium | Major export zone to China |

| Wa State | Wa Army (Pro-China) | REE reserves | Secured alternate supply lines |

| Shan State | Mixed militias | Light rare earths | Potential fallback mining base |

As conflict dynamics shift, China is not waiting for peace—it’s actively shaping the battlefield to protect its access.

📈 Rare Earths and Global Tech Supply Chains

Rare earths are the invisible engines of the tech world. From iPhones to F-35 fighter jets, they power tools that run economies and define military advantage.

🌐 Countries most dependent on rare earths:

- United States: ~80% of imports from China

- Japan: ~60% from China, including components via third countries

- India: Increasing domestic mining, but imports still dominate high-end processing

If China’s Myanmar supply were cut off entirely, prices for dysprosium and terbium could spike globally, sending shockwaves across EV, solar, and defense industries.

This is why the U.S., EU, and India are racing to:

- Diversify sources (Africa, Australia, Greenland)

- Invest in processing capacity

- Recycle rare earths from e-waste

- Partner with ASEAN countries to counterbalance China’s grip

🤔 Did You Know?

China used rare earths as a political weapon once before—in 2010.

After a maritime dispute with Japan, China cut off rare-earth exports, causing global panic and price spikes. The move was a wake-up call, and it’s why nations now view rare earths as critical national security assets, not just trade goods.

🌏 Strategic Implications: It’s Not Just About Minerals

The Myanmar-China mineral nexus is a textbook case of resource weaponization. It reveals how:

- Mineral dependencies shape foreign policy

- Rebel groups become geopolitical influencers

- Conflict zones impact clean energy goals worldwide

It also underlines the growing risk that as the world transitions to green energy, the control over mineral inputs becomes the new oil politics—and China is positioning itself as the OPEC of rare earths.

🔮 What Comes Next?

Unless the conflict in Myanmar stabilizes or China finds a way to secure alternate sources:

- We can expect price volatility in heavy rare earths

- China may expand stockpiling and subsidy programs

- Western nations could accelerate partnerships with India, Vietnam, and Africa

- Myanmar’s internal instability will continue to attract external interference

The EU, U.S., and Quad nations may also increasingly view critical mineral corridors like Myanmar as strategic frontlines in the tech cold war with China.

🧠 Conclusion: When the Mines Shape the Map

This isn’t just a story about minerals or militias—it’s about how resource power is reshaping global politics.

China’s deepening grip on rare-earth supplies via Myanmar highlights a new form of conflict—where access to dysprosium or terbium may matter as much as access to oil fields once did.

In the years ahead, wars may be won not just with weapons—but with contracts, smelters, and supply routes. And Myanmar, despite its instability, sits right at the center of this high-stakes mineral map.

+ There are no comments

Add yours