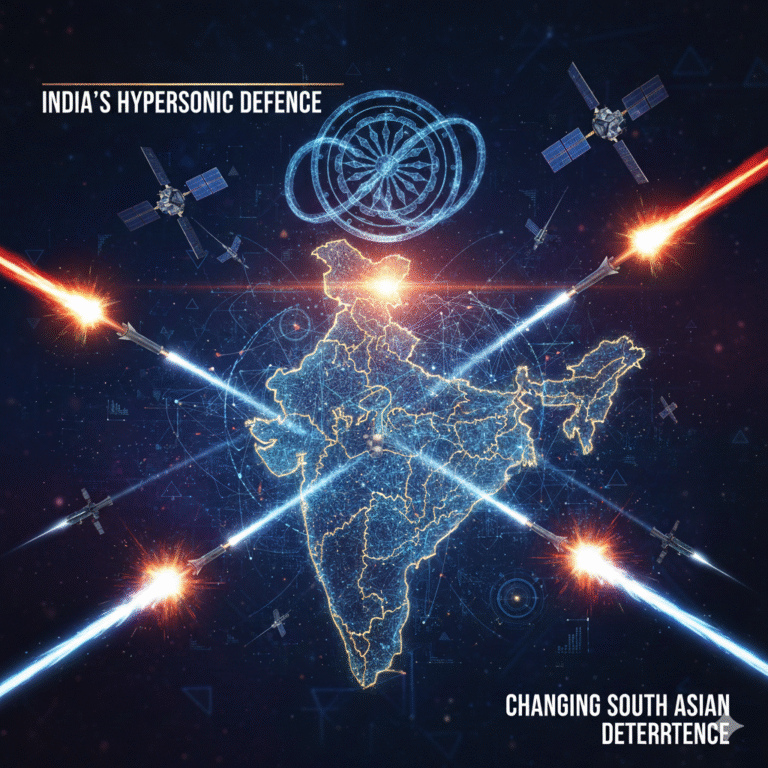

A silent conflict is unfolding above Earth, far from the public eye. In late June 2025, Russia deployed its military satellite, Kosmos‑2558, which quietly released a subsatellite, Object C, in close proximity to the U.S. spy satellite USA‑326. While such maneuvers have occurred before, the timing and precision of this orbital shadowing have renewed global fears about the weaponization of space.

These “inspector” satellites, while officially described as surveillance or diagnostic tools, may possess kinetic or electronic warfare capabilities. Their proximity to high-value American assets has raised alarm bells within military and intelligence circles worldwide.

The Strategic Significance of Kosmos-2558 and Object C

The deployment of Kosmos-2558 is not an isolated incident. Over the past five years, Russia has regularly launched satellites designed to approach, track, and potentially interfere with foreign space assets.

Why This Move Matters:

- USA-326 is believed to be a next-generation optical reconnaissance satellite launched by the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO).

- The maneuver of Object C near USA-326 is viewed as a potential rehearsal for anti-satellite (ASAT) warfare.

- Such moves threaten the norm of passive cohabitation in space and challenge the notion that outer space is a demilitarized zone.

According to open-source space tracking agencies, Object C has repeatedly adjusted its orbit to maintain a close and consistent position relative to USA-326, a sign of intent rather than coincidence.

The Rise of Anti-Satellite Capabilities

Russia is not alone in developing anti-satellite systems. China, the U.S., and India have also tested or deployed ASAT technologies. However, Russia’s orbital inspector satellites represent a stealthier and more persistent threat.

Types of ASAT Systems:

- Kinetic-kill vehicles: Destroy satellites by physical collision (e.g., China’s 2007 test).

- Co-orbital ASATs: Satellites that maneuver close to targets, capable of jamming, laser dazzling, or kinetic interference.

- Ground-based lasers or missiles: Disrupt or destroy satellites from Earth.

What makes Russia’s Object C notable is its multi-functionality and ambiguity. Its true purpose remains speculative, enabling Moscow to operate under the radar of current international space laws.

International Law and the Grey Zone

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, ratified by most spacefaring nations, prohibits the placement of weapons of mass destruction in orbit but is vague on the use of conventional weapons or proximity maneuvers.

Current Legal Gaps:

- No binding definitions of “hostile behavior” in space.

- No mandatory transparency for satellite maneuvers.

- No framework to inspect or verify suspected ASAT capabilities.

This grey zone enables countries like Russia to conduct provocative space activities without crossing legally defined “red lines.”

U.S. and Global Responses

The U.S. Department of Defense has reportedly increased surveillance and maneuverability options for key satellites. There are also calls for:

- Norm-setting dialogues at the UN and multilateral forums.

- Improved satellite situational awareness through AI and shared tracking.

- Hardened satellite architectures resistant to jamming or kinetic interference.

- Alliances for space defense under NATO or QUAD umbrellas.

A bipartisan U.S. Congressional group is pushing for an international “Space Conduct Code” akin to maritime laws.

The Strategic Stakes

Satellites today are not just about surveillance. They enable:

- Military communication and battlefield coordination

- GPS navigation for civilians and defense forces

- Weather monitoring and disaster response

- Global internet connectivity and economic activity

The loss or disruption of even a few satellites could cripple a nation’s command-and-control infrastructure, create dangerous orbital debris, and set off escalatory responses on Earth.

Looking Ahead: Diplomacy or Escalation?

The emergence of close-proximity ASAT maneuvers like those between Kosmos-2558/Object C and USA-326 is a red flag for policymakers. With space becoming increasingly crowded and contested, there’s an urgent need to:

- Define responsible behavior in orbit

- Establish norms for proximity operations

- Promote international transparency and verification mechanisms

Failing to act could lead to a future where space becomes not a domain of cooperation, but one of perpetual surveillance and latent conflict.

Conclusion

Russia’s orbital games near USA-326 are more than a geopolitical flex — they are a signal of a broader, more dangerous shift in the space domain. As countries compete for orbital supremacy, the stakes go beyond pride or technology. The future of global security, communication, and even daily life depends on the safety of our satellites.

We must act now to ensure that space remains a realm of peace — not the next battlefield in a new cold war.

+ There are no comments

Add yours